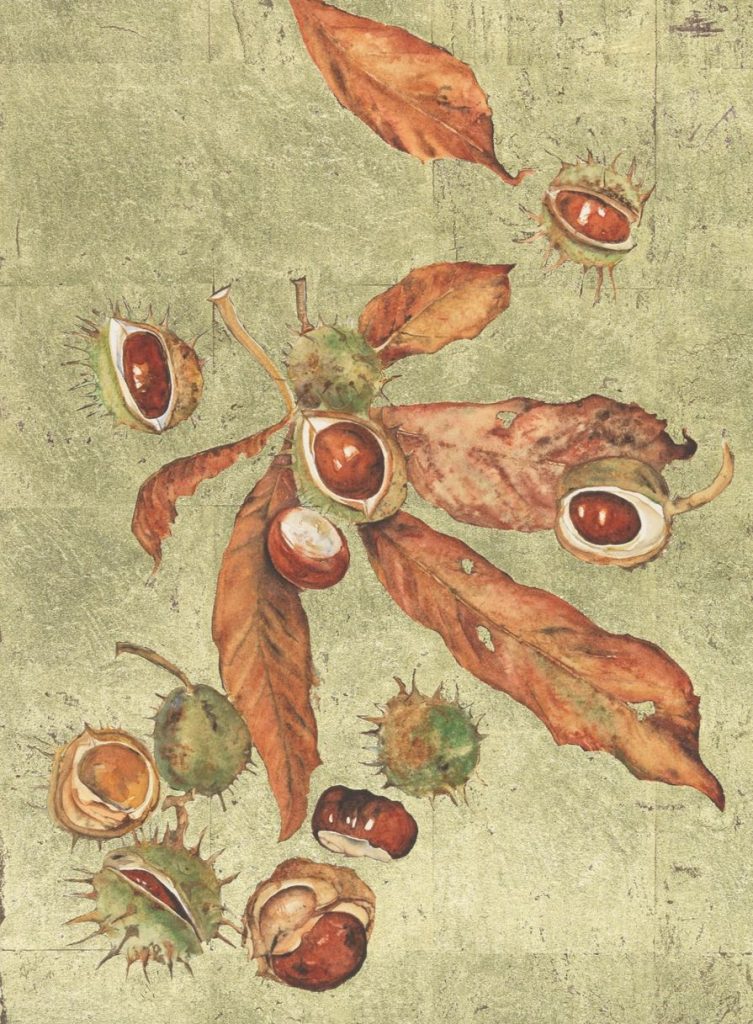

Often the first to be in full leaf, the horse chestnut trees are already looking rusty and worn, as if they simply haven’t got the energy to go on. No wonder really, considering what they’re making: thousands of spiked, green cannonballs with mahogany works of art inside.

Conkers! I still get excited about conkers. The silky sheen, the subtle rippling of deep purplish brown, like muscles moving under the skin of a racehorse. And that smell. Is any scent cleaner, greener, more distinctive than the inside of a conker shell? Breaking in to witness the way the nuts fit inside that pale interior, is like being told a great secret, a spell of happiness.

When I was little, six, seven, eight, I was obsessed with conkers. I dreamt of finding giant, perfect specimens, and I would open one spikey shell after another, always hoping that this would be the one. The truth was of course that they were all the one, each miraculously perfect. I tried every way I could to preserve the plump sheen, pickling, varnishing, drying in the oven, painting with oil. Nothing worked. The beauty and delight of conkers was transitory. They withered and shrivelled and for a while I mourned over the bowls of faded loveliness. And then I threw them out on to the compost heap, and turned my attention to the next round of seasonal delights: kicking fallen leaves; frost on spider webs; ice.

Where did I learn my conker obsession? I’m not sure. I didn’t grow up with siblings or friends but I did have a grandfather and a father who were passionate gardeners and who were always outside. I tagged along. I think my Dad was as mad about conkers as I was. He was the one who helped try to preserve them. As a kid I think he’d played ‘conkers’ and, now I think of it, I remember him stringing one for me, making a hole with a meat skewer on the kitchen table. It seemed like mutilation to me, and I had no interest at all in bashing things.

My awareness of nature was partly learned and partly acquired simply because I was outside all the time and curious, like all children; I looked, I touched, I sniffed I poked things with sticks (not the same as bashing).

Conker obsession was the norm back then. Come late September and October any conker tree was a magnet for children. Trees in parks were surrounded, the way lamps were crowded with moths. Kids gleaning amongst the leaves, kids throwing sticks to bring down the big, tantalising, out of reach fruits, high up. Even trees in the middle of nowhere would magically acquire a little tribe of worshiping children.

But not now. My last house was in a town and set in parkland. Seven or eight huge conkers trees stood on the edge of the paths or in the middle of the lawns, freely available to the many children who lived on the estate. In five years I saw two boys, once, collecting conkers. They kicked around in the leaves for ten minutes or so then gave up and drifted off.

What’s happened? Why can’t kids feel the conker magic any more?

There are a lot of answers to that question. Screens and perceived danger are some of the story: adults like their kids to be inside where they can easily keep an eye on them and still pursue their own screen obsession. A lack of un-structured wild space is another – there are sports grounds, there are play areas but there are fewer bits of long grass and bramble, trees that don’t belong to anyone – the liminal, un-used spaces, that have in the past been the territory of children.( see Julia Green’s wonderful The Wilderness War for a novel about this)

It’s not that children have lost a taste for nature. It’s what I write about and I’ve never been into a school where my subject  matter wasn’t received with huge enthusiasm. Kids know and love elephants and lions, orang utans and giraffes. They can tell you how big a blue whale is. But they haven’t a clue what a conker is, or what a wren sounds like. And mostly these days, neither have their teachers.

matter wasn’t received with huge enthusiasm. Kids know and love elephants and lions, orang utans and giraffes. They can tell you how big a blue whale is. But they haven’t a clue what a conker is, or what a wren sounds like. And mostly these days, neither have their teachers.

The problem, I think, is a kind of collective forgetting. It only takes one generation of parents forgetting their own childhoods, forgetting dens and tree climbing, acorn gathering, puddle splashing and leaf kicking, bramble picking, for the cultural transmission of nature-delight to be lost. And with that forgetting comes a loss of the language we use to describe those experiences. How do you point out an oak tree to a child, if you don’t know the word ‘oak’ or ‘acorn’ or even tree? How do you even notice an ask or an ash, a pine or a willow if the only word you know is tree?

Imagine that no one in your family had ever made a birthday cake. Your grandmother made one with her dad once, but your parents never did. They don’t know how to do it. They don’t even know the words to describe what goes into a cake. So cakes drop out of the world because no one knows the words, ‘butter’, ‘sugar’, ‘eggs’, ‘chocolate’ ,‘candle’, ‘icing’ ,‘mix’, ‘bake’.

That’s what we are on the brink of. Losing touch with our ordinary, everyday, infinitely precious back yard wild, because we are losing the language to name it. Many adults and children no longer know words that specify anything more particular than ‘plant’ or ‘bird’.

This matters. The evidence is mounting that this loss of connection, this loss of ability to articulate to ourselves and others the detailed, particular experience of the natural world is damaging us. Is damaging our children. Development and long term mental health are at risk without contact with nature. Disorders like ADHD, depression and anxiety are all healed by nature, by willow and ivy, by acorn, bluebell and bramble, by wren and starling, heron and kingfisher.

Which is why, back in 2015 I was signatory to a letter, ( see below) written by Lawrence Rose to OUP protesting that the new edition of the junior oxford dictionary had removed many words for features of the natural world, words like acorn, and willow and wren. OUP’s response was merely to repeat a description of what they do and to say that they were just reflecting the word usage of modern children. But the tone of their response (which you can also read below) was very much that of responsible moral and cultural educators. If that’s what they are, then they are duty bound not to rob children of words which can describe common features of the world around them. Removing these words removes children’s ability to recognise and take ownership of common plants and animals that are their natural and also their cultural heritage. Every child in Britain deserves to know, and to see bluebells, as much as they deserve to know about the science, the art, the technology and the history that has made us all who we are. And they can’t do that without the language to do it.

Which is why, back in 2015 I was signatory to a letter, ( see below) written by Lawrence Rose to OUP protesting that the new edition of the junior oxford dictionary had removed many words for features of the natural world, words like acorn, and willow and wren. OUP’s response was merely to repeat a description of what they do and to say that they were just reflecting the word usage of modern children. But the tone of their response (which you can also read below) was very much that of responsible moral and cultural educators. If that’s what they are, then they are duty bound not to rob children of words which can describe common features of the world around them. Removing these words removes children’s ability to recognise and take ownership of common plants and animals that are their natural and also their cultural heritage. Every child in Britain deserves to know, and to see bluebells, as much as they deserve to know about the science, the art, the technology and the history that has made us all who we are. And they can’t do that without the language to do it.

In my work, it’s hard for me to write about the nature that surrounds me here in Wales, the plants and birds, mammals and reptiles that I’ve loved all my life living in the UK. I write picture books mostly and they need foreign co -edtions. Much as I’d love to write about rooks and slow worms, the perception of editors is that those books wouldn’t sell in the USA or China. So, the nearest I’ve come to helping with reconnecting kids and their parents with the nature on their doorstep is A First Book Of Nature a collection of poems illustrated by the quintessentially British images of Mark Hearld. I’ve done a little to help with the issue of the importance of naming species to maintain biodiversity, with a new book for Hodder, illustrated by Lorna Scobie the Variety of Life (which I’ll blog about soon).

But prompted by OUP’s editorial decision to remove some essential words for nature, my great friend and mentor Jackie Morris, together with writer Robert MacFarlane, have done a much better job. They have struck a resounding blow in the battle to maintain the richness of our nature language and our right to access and describe our experience, with their book ‘The Lost Words’. Robert’s poems create spells and charms to conjure and celebrate each of the animals and plants whose names have been lost from the junior dictionary. Jackie’s ravishing pictures show each species in beautiful detail and in context of their habitat, eloquently representing what each loss would mean.

It’s an extraordinary book. I’ve adored watching it grow over the last two years, but its more than a publishing phenomenon, it’s going to make a difference. I think could prove to be a landmark in the rewilding of parents, children, childhood and lives. We need the wild, and, we need the words to hold it like a heartbeat inside us all the time. As Yeats said, in my father’s favourite poem, The Lake Isle of Innisfree we need to hear it ‘in the deep heart’s core.’

Jackie and I will be talking about The Lost Words at the Crickhowell Literary Festival on Saturday October 7th, do join us!

THE LETTER TO OUP

Oxford University Press as e-mail attachment 12 January 2015

Reconnecting kids with nature is vital, and needs cultural leadership

We the undersigned are profoundly alarmed to learn that the Oxford Junior Dictionary has systematically been stripped of many words associated with nature and the countryside. We write to plead that the next edition sees the reinstatement of words cut since 2007.

We base this plea on two considerations. Firstly, the belief that nature and culture have been linked from the beginnings of our history. For the first time ever, that link is in danger of becoming unravelled, to the detriment of society, culture, and the natural environment.

Secondly, childhood is undergoing profound change; some of this is negative; and the rapid decline in children’s connections to nature is a major problem.

This is not just a romantic desire to reflect the rosy memories of our own childhoods onto today’s youngsters. There is a shocking, proven connection between the decline in natural play and the decline in children’s wellbeing. Compared with a generation ago, when 40% of children regularly played in natural areas, now only 10% do so, while another 40% never play anywhere outdoors. Ever. Obesity, anti-social behaviour, friendlessness and fear are the known consequences. The physical fitness of children is declining by 9% per decade, according to Public Health England.

For the first time ever, children’s life expectancy is lower than that of their parents – us.

When, in 2007, the OJD made the changes, this connection was understood, but less well publicised than now. The research evidence showing the links between natural play and wellbeing; and between disconnection from nature and social ills, is mounting.

We recognise the need to introduce new words and to make room for them and do not intend to comment in detail on the choice of words added. However it is worrying that in contrast to those taken out, many are associated with the interior, solitary childhoods of today. In light of what is known about the benefits of natural play and connection to nature; and the dangers of their lack, we think the choice of words to be omitted shocking and poorly considered. We find the explanations issued recently too narrowly focussed on a lexicographical viewpoint without consideration for the social context.

In all, the names for thirty species of common or important British plants and animals have been removed – such as acorn and bluebell – along with many words connected with farming and food. Many are highly symbolic of our cultural ties with the land, its wildlife and produce.

This is what the National Trust says in their Natural Childhood campaign: Every child should have the right to connect with nature. To go exploring, sploshing, climbing, and rolling in the outdoors, creating memories that’ll last a lifetime. Their list of 50 things to do before you’re 11 3?4 includes many for which the OJD once had words, but no longer: like playing conkers, picking blackberries, various trees to climb, minnows to catch in a net and so on.

The RSPB has commissioned a great deal of research on this. Among many findings is the fact that outdoor activity in nature appears to improve symptoms of ADHD in children by

30% compared with urban outdoor activities and 300% compared with the indoor

environment.

It is no surprise that these and other organisations, including the NHS and Play England,

Play Scotland and Play Wales have come together to create The Wild Network dedicated to

reconnecting children and their families to nature – and to each other.

Will the removal of these words from the OJD ruin lives? Probably not. But as a symptom

of a widely acknowledged problem that is ruining lives, this omission becomes a major issue.

The Oxford Dictionaries have a rightful authority and a leading place in cultural life. We

believe the OJD should address these issues and that it should seek to help shape

children’s understanding of the world, not just to mirror its trends.

.

We believe that a deliberate and publicised decision to restore some of the most important

nature words would be a tremendous cultural signal and message of support for natural

childhood, and we ask you to take that opportunity, and if necessary, bring forward the next

edition of the OJD in order to do so.

Margaret Atwood

Author

Simon Barnes

Author and journalist

Terence Blacker

Writer and songwriter

Mark Cocker

Author and naturalist

Miriam Darlington

Author

Nicola Davies

Children’s author

Paul Farley

Poet, writer and broadcaster

Graeme Gibson

Novelist

Melissa Harrison

Writer

Tony Juniper

Writer and ecologist

Richard Kerridge

Nature writer

Gwyneth Lewis

Former Welsh Poet Laureate

Sir John Lister-Kaye

Naturalist and author

Richard Mabey

Writer and naturalist

Robert Macfarlane

Writer and academic

Helen Macdonald

Writer, illustrator and historian

Sara Maitland

Writer

Mike McCarthy

Nature writer

Hilary McKay

Children’s writer

Andrew McNeillie

Academic, former OUP Literature Editor

Sara Mohr-Pietsch

Broadcaster

Michael Morpurgo

Author, former Children’s Laureate

Jackie Morris

Children’s book illustrator

Stephen Moss

Naturalist, author and TV producer

Sir Andrew Motion

Former Poet Laureate

Ruth Padel

Poet and conservationist

Jim Perrin

Travel writer

Katrina Porteous

Poet, historian and broadcaster

For correspondence:

Laurence Rose laurence@naturemusicpoetry.com

…AND OUP’S RESPONSE

Editor, NATURAL LIGHT

Statement from Oxford University Press – 13 January 2015

“Oxford University Press (OUP) is renowned around the world for its high quality educational and scholarly publishing. Our children’s dictionaries, of which there are 17 in the UK alone, are structured by age, with each dictionary specifically written with a certain age group in mind, and with headwords and levels of definition varying according to what that child will need most at any given age.

“All our dictionaries are designed to reflect language as it is used, rather than seeking to prescribe certain words or word usages. We employ extremely rigorous editorial guidelines and word selections are based on several criteria: the current frequency of words in the daily language of children of that age; children’s culture including their reading of fiction and non-fiction; corpus analysis* and commonly misspelled or misused words. We also take current curriculum requirements into account. These criteria then need to be balanced against the appropriate length of any given dictionary, to create accessible resources appropriate for the age of the child the particular dictionary is aimed at.

“The Oxford Junior Dictionary, which was last updated in 2012, is aimed at six to seven-year-olds with 288 pages and approximately 4,700 headwords. As such it is very much an introduction to language. It includes around 400 words related to nature including: badger, bean, bee, berry, branch, caterpillar, daffodil, dragonfly, duck, feather, field, fox, grasshopper, hay, hedge, hedgehog, hibernate, invertebrate, meadow, mouse, nut, oak, owl, pear, plum, robin, seed, shell, sheep, snowflake, squirrel, stag, stone, straw, sunflower, tadpole, vegetation, and wool.

An example entry is:

hibernate verb, hibernates, hibernating, hibernated

When animals hibernate, they spend the winter in a special kind of deep sleep. Bats, tortoises, and hedgehogs all hibernate.

“As children get older they will progress to the Oxford Primary Dictionary aimed at eight to eleven- year-olds. This has 608 pages and 12,000 headwords and it contains all of the words that have been recently highlighted and many, many more.”

“We have no firm plans to publish a new edition of the Oxford Junior Dictionary at this stage. However, we welcome feedback on all our dictionaries and feed this into the editorial process.”

ENDS

*The Oxford Children’s Corpus is a unique database of over 150 million words used in reading and writing for and by children. Our dictionary team uses the Oxford Children’s Corpus to research how children read and use language and to ensure our dictionaries are age-appropriate and up-to-date as language usage changes. It also helps us identify new or re-emerging word trends, words they find tricky to spell, and common issues with grammar and punctuation.