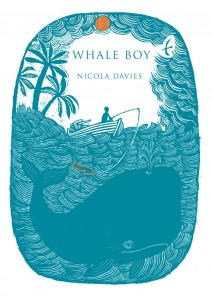

Whale Boy is out on April 4th and even though I’ve had lots of books published, publication day is still special. Once a book is out in the world, it can begin to speak to readers. And I have great hopes of what ‘Whale Boy’ has to say.

Whale Boy is out on April 4th and even though I’ve had lots of books published, publication day is still special. Once a book is out in the world, it can begin to speak to readers. And I have great hopes of what ‘Whale Boy’ has to say.

The title of ‘Whale Boy’ tells you pretty much what this book is about – a whale, in this case a young, wild, male, sperm whale, and a boy, Michael, who lives on a fictionalized Caribbean island. I’ve spent some of the happiest times of my life on board small boats in tropical sees watching whales and I wanted to put the delight of those experiences and close encounters into the book. Friendship with a wild animal is what I dreamed of most when I was little and I have enough contact with kids to know that many children today share that dream. So I’m hoping readers will relish the time that Michael spends in the company of his whale, and take those moments to their hearts. But ‘Whale Boy’ does not end in the way that many child and animal stories do. I won’t give anything away here in case you want to read it and haven’t yet, but I will tell you a bit about what motivated me to write that ending, so you’ll understand when you get there.

Whales and dolphins – cetaceans – have always had a special status in the hierarchy of wild creatures. Dolphins particularly have been considered intelligent and friendly for hundreds if not thousands of years; not just another creature. But in my lifetime whales and dolphins have acquired the status of religious icons, not only symbols of imperiled nature, but the embodiment of Mother Earth, a channel for the spiritual power of the universe. I’ve seen people play musical instruments to whales, sing to them, talk to them, swim with them, and I’ve heard people claim to be cured of every ailment from depression to cancer by contact with whales or dolphins. Businesses have grown up around these beliefs and every year thousands of people climb aboard boats, put on wetsuits or stand in the shallows waving a dead fish, in order to commune with some kind of cetacean.

Now I don’t dispute the cures, the benefits, the joys, the spiritual highs; for me, having a close encounter almost any wild animal is enough to keep me smiling and inspired for days, weeks, months even. That contact is in many ways the engine that drives my entire life. But I do have a question and that is ‘what are the consequences for whales and dolphins of close contact with humans?’ I’m pretty sure a dolphin never claimed that smooching up to a human twelve year old healed a shark bite, or that a humpbacked whale never had a moment of life changing insight after swimming with a dentist from Milwaukee.

smiling and inspired for days, weeks, months even. That contact is in many ways the engine that drives my entire life. But I do have a question and that is ‘what are the consequences for whales and dolphins of close contact with humans?’ I’m pretty sure a dolphin never claimed that smooching up to a human twelve year old healed a shark bite, or that a humpbacked whale never had a moment of life changing insight after swimming with a dentist from Milwaukee.

What do cetaceans get out of our desire to be close to them? Well one thing they get is captivity. Even at its best and most closely monitored and regulated, captivity in a pool, for a creature whose natural environment is limitless, is not really acceptable. And remember, for every big, clean dolphinarium, there are at least twenty small, dirty, miserable little ponds where dolphins swim in circles for a few months and then die.

Another thing they get is disturbance. Harassment by boats can disrupt natural behavior and even put whales at risk of injury from collision with propellors or other boat gear. Motor boat noise is a potential source of disruption too as whales and dolphins depend on sound for echolocation and communication. When cetaceans already have to put up with all our noise and bother in the sea, as we transport goods around the globe or sonic ping the depths in search of minerals and oil, do we also have to pursue them in our spare time?

Swimming away is of course always an option, but this may cause a cetacean to use up valuable energy, or miss out on opportunities to feed or mate. One solution is to habituate cetaceans to human presence, or offer them a food reward. But even this can skew their behaviour in negative ways. In Western Australia, offspring of habituated dolphins show lower rates of survival than those of adults who have no contact with humans.

In Baja California grey whales on their breeding site seem to be the ones initiating contact with humans in boats. Boats wait, grey whales approach and if the occupants of the boat don’t interact, they move on. But this is a very special case. Contact in the breeding lagoons is pretty well regulated and grey whales have a very predictable migration route up the West coast of the United states, along whose entire length they are protected. If grey whales think of humans as benign, they aren’t going to come to much harm.

For sperm whales, the species that I’ve been most involved with since 1984, helping out on my old friend’s research vessels in the Indian Ocean, Mexico and the Caribbean, the situation is very different. Sperm whales aren’t migratory, they’re just nomadic and wander, often very unpredictably, over whole oceans. The males especially travel over vast distances, that may span the tropics to the poles and back again many times in their long lives. They encounter all kinds of vessels from huge tankers to little fishing boats, and all kinds of people from round the world, yachtsmen to pirate whalers. For sperm whales to regard humans as benign is simply dangerous: for the whales because they won’t always encounter well meaning humans; for humans because getting close to an animal the size of a bus is risky. The safest attitude for a sperm whale to take to any kind of human is one of deep suspicion and constant wariness.

For sperm whales, the species that I’ve been most involved with since 1984, helping out on my old friend’s research vessels in the Indian Ocean, Mexico and the Caribbean, the situation is very different. Sperm whales aren’t migratory, they’re just nomadic and wander, often very unpredictably, over whole oceans. The males especially travel over vast distances, that may span the tropics to the poles and back again many times in their long lives. They encounter all kinds of vessels from huge tankers to little fishing boats, and all kinds of people from round the world, yachtsmen to pirate whalers. For sperm whales to regard humans as benign is simply dangerous: for the whales because they won’t always encounter well meaning humans; for humans because getting close to an animal the size of a bus is risky. The safest attitude for a sperm whale to take to any kind of human is one of deep suspicion and constant wariness.

So when my friend, Professor Hal Whitehead, is studying sperm whales he keeps his vessel at a respectful distance, so as not to get in the whales’ way and uses sail rather than motor power whenever possible. Even so, there are times when the temptation to get very close to the whales is huge: young sperm whales, particularly young males, are very curious and will approach boats very closely. Looking down into the eye of a whale that is swimming round and round your boat, so close you could reach over side and touch it, really makes you want to get in the water with it; the whale itself seems to want you to. But every time this happens, what you have to ask is ‘ what good would it do the whale?’, and resist!

In Dominica, where I last spent time with sperm whales, there is a big temptation for people to try to get very close to the sperm whales that are found off the coast there. Every year more tourists come to see the sperm whales, and more boats promise to get them ever closer. Dominicans are not selfish or money grabbing but they are very proud of their whales and want to show them off to visitors. Whale watching operations bring people in boats very close to the whales, and even put tourists in the water with them. So although no one in Dominica has to face the dramatic decisions that Michael has to, perhaps someone needs to be asking what good do these activities do for whales? For example, would people be less likely to give to ocean conservation charities if they had got within 200m of a sperm whale rather than within 20 m? You wouldn’t expect to get out of your land rover and run over the Serengeti Plains with a cheetah, so why would expect to do something similar with a wild whale?

If you read the book you’ll see how all these thoughts played out in my mind as I wrote it, but of course they weren’t the only ingredients I used in telling Michael’s story. Every page has been marinaded in the sunlight, the warmth and the huge sense of community that exists in the Commonwealth of Dominica. Dominica is a truly extraordinary place; it has a population small enough for everyone to feel they have an identity as part of the country. That’s something we’ve lost in most parts of the UK and I really wanted to give my readers a taste of that sweetness of Dominican society. The importance of community and of home is expressed in so many things, even the way Dominicans fish: ‘always home at night to see their women’ as one fishery official told me, or sharing the work and the catch from spreading a net across a bay. So fishing was another important flavour in Michael’s story. The many stories of separation that can be found across the Caribbean, as people left to find work and new lives in the UK, America and all over the world, gave me another important strand. I met many people with family members abroad, and Dominicans who had come home after decades away, making a living in London or New York. At Carnival, the plane from London was full of excited Dominicans going home for the celebrations and I heard their stories of coming to cold, grey England from a childhood of sunlight and colour.

So many good things happened to me in Dominica, so many chance encounters and moments of shared laughter. It is the most loving place I’ve ever been to, so it’s not surprising that ‘Whale Boy’ is also about love, and how, when you love someone or something, you’ll do whatever it takes to protect it. That’s the discovery that Michael makes. But if you want to know more, you’ll have to read it!