When I was 17 I bought an album that wasn’t anything like the LPs that my friends talked about on the bus to school. Rather than moody, unsmiling, adolescent boys, its cover featured an artwork of a breaching whale. I played it for the first time on my father’s radiogram, at night, lying flat on the floor and staring into the darkness. High sweeping moans, bubbling rumbles, whoops and squeaks came from the record, sounds unlike those made by any human instrument, and yet this was quite obviously music. It spoke straight to my heart and I was instantly besotted. Over the next three years ‘The Song of the Humpback Whale’ recorded by American biologist, Roger Payne, became the soundtrack of my journey from school girl to fledgling biologist.

When I was 17 I bought an album that wasn’t anything like the LPs that my friends talked about on the bus to school. Rather than moody, unsmiling, adolescent boys, its cover featured an artwork of a breaching whale. I played it for the first time on my father’s radiogram, at night, lying flat on the floor and staring into the darkness. High sweeping moans, bubbling rumbles, whoops and squeaks came from the record, sounds unlike those made by any human instrument, and yet this was quite obviously music. It spoke straight to my heart and I was instantly besotted. Over the next three years ‘The Song of the Humpback Whale’ recorded by American biologist, Roger Payne, became the soundtrack of my journey from school girl to fledgling biologist.

But in 1970s Britain whales were impossibly distant, away in the realm of dragons or unicorns. Something to campaign about – whaling was still alive, well and legal back then- or dream about, but not, I thought, creatures I could ever really see or study. Then, quite by chance, in my second year at university, I met Hal Whitehead. In whaley-circles nowadays that name is legendary, but back then, Hal wasn’t Professor Whitehead, the most eminent whale biologist of his generation, but a scruffy post doc, looking for a research assistant – and that turned out to be me.

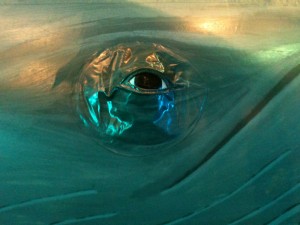

So, in June 1979 I stood on a cliff in Newfoundland and looked down to see three humpback whales in the water below, their fins showing turquoise through the jade-coloured ocean. I spent two summers there, studying humpback feeding behaviour, as they hoovered up the shoals of spawning capelin that lay just under the surface, like heaped hoards of silver doubloons. They breached, just like the whale on the album cover, sometimes multiple times. One whale did 47 breaches in a row, although by the time it did the last one, it wasn’t getting very far out of the water. When the sea mist rolled in and brimmed to the cliff top like milk, I’d listen to their blows and snorts carrying up from the water below.

So, in June 1979 I stood on a cliff in Newfoundland and looked down to see three humpback whales in the water below, their fins showing turquoise through the jade-coloured ocean. I spent two summers there, studying humpback feeding behaviour, as they hoovered up the shoals of spawning capelin that lay just under the surface, like heaped hoards of silver doubloons. They breached, just like the whale on the album cover, sometimes multiple times. One whale did 47 breaches in a row, although by the time it did the last one, it wasn’t getting very far out of the water. When the sea mist rolled in and brimmed to the cliff top like milk, I’d listen to their blows and snorts carrying up from the water below.

At the end of the first of my two Summers in Newfoundland, and almost as exciting as seeing real live humpbacks, I met Roger Payne and his musicologist partner Katy, who did much of the work on humpback song. I spent an afternoon – entirely overawed and star struck – at their ‘lab’ outside Boston. I remember a light filled loft, surrounded by trees; green, leafy-light streaming in and falling on huge worktops, covered in sonograms of whale song; intense grad students arguing about what humpbacks did and didn’t do in the warm tropical waters where they courted and had their calves.

The research that Katy and Roger began has now grown into decades of recordings of humpback song from around the world. It’s shown that humpback song is the most complicated display created by any animal. But unlike bird song or courtship display, it changes, sometimes quite radically, not because of genetic change but because whales learn from and react to each other. All male humpbacks in one place sing the same song each year but by the following year, perhaps a new ‘verse’ or a different ‘chorus’ has been added. Gradually some of these changes spread across oceans from one population to another, usually in a predictable direction and at a steady speed. And once in a few years there is a huge song-shift and another, very different , song takes over, completely replacing the original song. As if the all whales suddenly decide to stop singing Beyonce and switch to Adele, or even Beethoven. In other words humpback song can change not because of evolution but because of revolution – a change is as much cultural as human changes in musical tastes.

Throughout my two summer studying humpbacks I dreamed longing dreams about tropical oceans, filled with whale song and I wanted more than anything in the world to see and hear humpbacks living their other, more beautiful, romantic life. But humpbacks only sing on their winter breeding grounds, and I had to wait thirty years before I was finally heard humpbacks sing.

In 2013 I was, at last, back on another of Hal’s research boats, ‘Baleana’, in the deep waters off the Caribbean island of Dominica. It was captained by Hal’s research partner Shane Gero, who runs the long term study of sperm whales there, so humpbacks were not really on the agenda. It was almost the last night of my two week stay and I was on watch in the wee small hours. Black water lapped around the boat, the sky was streaked with navy blue clouds and veiled stars. A hydrophone over the side allowed us to eavesdrop on what was going on in the ocean beneath us and part of my job on watch was to listen out for sperm whale clicks, at regular intervals. I put on the headphones and shut my eyes. There were the familiar noises – dolphin whistles, thin high wisps of sound and the frantic clock ticking noises that announced that a pod of sperm whales was hunting somewhere a thousand meters under our keel. But then a new sound, one I hadn’t heard at all before but instantly recoginized, an ascending keening-curve of sound, a rumble, a running series of short whoops and long, low note, off the lowest register of an oboe. Humpback song! Almost as soon as I heard the first, there was a second. The song soaked into me and I knew that somewhere inside, I had been hungry for this sound for every second of those thirty years. I felt as if it was entering every cell and settling into my DNA like a new bit of code.

In 2013 I was, at last, back on another of Hal’s research boats, ‘Baleana’, in the deep waters off the Caribbean island of Dominica. It was captained by Hal’s research partner Shane Gero, who runs the long term study of sperm whales there, so humpbacks were not really on the agenda. It was almost the last night of my two week stay and I was on watch in the wee small hours. Black water lapped around the boat, the sky was streaked with navy blue clouds and veiled stars. A hydrophone over the side allowed us to eavesdrop on what was going on in the ocean beneath us and part of my job on watch was to listen out for sperm whale clicks, at regular intervals. I put on the headphones and shut my eyes. There were the familiar noises – dolphin whistles, thin high wisps of sound and the frantic clock ticking noises that announced that a pod of sperm whales was hunting somewhere a thousand meters under our keel. But then a new sound, one I hadn’t heard at all before but instantly recoginized, an ascending keening-curve of sound, a rumble, a running series of short whoops and long, low note, off the lowest register of an oboe. Humpback song! Almost as soon as I heard the first, there was a second. The song soaked into me and I knew that somewhere inside, I had been hungry for this sound for every second of those thirty years. I felt as if it was entering every cell and settling into my DNA like a new bit of code.

Ever since, I’ve been planning to write something about humpback song and I’ve been looking for an opportunity to go back to a tropical ocean somewhere to hear it again. But a  unique collaboration between musicologists and biologists sciences, initiated by Dr Alexis Kirke senior research fellow at the School Of Humanites and Performing Arts at Plymouth University could give me an opportunity to hear it, closer to home.

unique collaboration between musicologists and biologists sciences, initiated by Dr Alexis Kirke senior research fellow at the School Of Humanites and Performing Arts at Plymouth University could give me an opportunity to hear it, closer to home.

Back in 2010 Alexis got interested in blue whale songs and the very precise pitching of their sounds http://www.sfsu.edu/news/prsrelea/fy10/002.html Reading the paper got him thinking “Shortly after” Alexis says, “I was sitting in a meeting and the director of Peninsula Arts said she wanted to commission a piece of music.I pitched the idea of the Saxophone and Blue Whales performance and got the gig.” As Alexis dived deeper into whale biology as part of his research for the piece he met biologist Simon Ingram who told him about humpback song, and introduced him to the whale science team at St Andrew’s University, lead by Dr Luke Rendel (Hal’s collaborator). The first result was a performance, ‘Fast Travel’ , that combined live saxophone performance with the singing of virtual whales, whose songs were programmed to react to the saxophone and to each other http://www.wired.co.uk/news/archive/2011-07/25/whale-song-alex-kirke The second result is a much larger, evolving collaboration between Alexis, Simon, Luke and their Phd Students. The plan is, Alexis explained, to “use the modelling of humpback whales as a way both to investigate their marine science and to develop tools for multi-robot system communication”

For the time being the focus is very much on the whales. The team aim to unravel some of the mysteries of humpback song, which have resisted almost four decades of scientific study: why and how does the song change over time and what exactly is the role it plays in the lives of humpback whales? Using models developed by Alexis’ team in Plymouth, computer programmes will mimic humpback songs, as described by hundred of hours of field studies and recordings. These programmes will create twenty, virtual whales – referred to in the study as ‘agents’ – who will sing in the virtual ocean of cyberspace and react to each others songs. The ‘agents’ can be imbued with different characteristics – a liking for new sounds or an aversion to them, for example- and the number of whales singing, their volume and spacing can also be varied. Six months worth of humpback singing can happen in cyberspace in just two minutes, so it will be possible for Luke and his collaborators to run hundreds of different virtual scenarios with the agents in their virtual ocean. “We hope” Luke told me” that we can generate a model that exactly mirrors the patterns of song evolution we see in real whale populations”.

As I talked with the team in Plymouth back in October we began to think about some possible spin offs from the project, things not strictly speaking part of the research… Could the virtual whale song be part of Plymouths annual festival of contemporary music? Could the whale song model be made into an app allowing people to run different whale song scenarios for themselves, and generate new kinds of songs? Could the songs be visually represented, like animated sonograms?

The ideas that got me most excited were, off course, the ones related to children. For years I’ve been ending almost every school visit or literary festival performance by teaching audiences of children a potted version off humpback song that they can reproduce easily. Of course, children love the opportunity to make loud noises – especially ones like farts – so this always goes down a storm. But could this be combined with Luke’s project in a more sophisticated way? One possibility would be to design an interactive app that allowed children to make their own whale songs using their own voices and then include them in a virtual song scene with other virtual whales, and see how those whales reacted to their song. Can you lure a whale closer with your song? How must you change your song composition to do this? Can you invent and sing a song, so popular it brings about a whale cultural revolution? This could be something that schools could run on a computer in class, as part of a science or a music lesson, or something that could run in a ‘Whale Song Booth ‘ at a cultural festival.

The ideas that got me most excited were, off course, the ones related to children. For years I’ve been ending almost every school visit or literary festival performance by teaching audiences of children a potted version off humpback song that they can reproduce easily. Of course, children love the opportunity to make loud noises – especially ones like farts – so this always goes down a storm. But could this be combined with Luke’s project in a more sophisticated way? One possibility would be to design an interactive app that allowed children to make their own whale songs using their own voices and then include them in a virtual song scene with other virtual whales, and see how those whales reacted to their song. Can you lure a whale closer with your song? How must you change your song composition to do this? Can you invent and sing a song, so popular it brings about a whale cultural revolution? This could be something that schools could run on a computer in class, as part of a science or a music lesson, or something that could run in a ‘Whale Song Booth ‘ at a cultural festival.

I’m also keen to explore some of the story possibilities of humpback song. Many of my own stories feature children who, in some way struggle to be heard, or whose voice, opinions, personality are at odds with those around them. So, there are some obvious parallels with humpback song. The surface of the water is an almost perfect barrier to sound so a whale can be singing in the water and inaudible in the air above. A child may be singing or crying on the inside but that emotional voice may be completely inaudible to the adults around her. A novel song may be ignored by a population of humpbacks, or bring about a revolution so that all whales sing the new song, just as a child, very different from her piers, may be the outcast or the most popular kid in class. I’m also very interested in the image of the singing whale as an archetype – a symbol of freedom and of the beauty of the wild. I have an image in my head of a child, frightened and alone, in a dark room reaching out to find a whale swimming close in the darkness.

The weekend after I met the two teams in Plymouth, I was playing around with a singing bowl filled with water, watching the water form a small fountain, simply with the sound waves produced by stroking the bowl around its edge. It got me thinking; humpback song is very loud and humpbacks hearing it are immersed in water. What effect does humpback song have on the water and on the whale bodies immersed in it? Could whales be perceiving their songs in a very different way from the way we choose to record and document them? Could the whales listening but not singing – the females- be conducting the sound in the way the bowl conducts the sound waves?

I’m just at the beginning of thinking about how a narrative with human meaning might be linked, counterpointed, harmonised, with the story of humpback song. Right now I have all sorts of things swimming around in my head, but I know that as always its as important to look out, as it is to look in when you search for stories. So I’m waiting to hear what Alexis, Luke and his collaborators discover when they begin to play with virtual whales, and looking forward to more cross curricular conversations between biology and music.

And I’m planning to go and hear humpback song in the wild again…I’m in need of new adventures.

DO READ

‘The Cultural Lives of Whales’, By Hal Whitehead and Luke Rendel from St Andrews University,