When I get asked about what I do, which isn’t very often, the conversation usually has a section in it that goes like this

When I get asked about what I do, which isn’t very often, the conversation usually has a section in it that goes like this

me: I write quite a lot of picture books

other person: ( ready to be very impressed) Oh do you do the pictures?

me: (a bit dejected here) No, no. Only the words

other person: (a bit embarrassed) Oh.

…and that’s where the conversation usually ends. They turn away. It’s as if I’d told them ‘I work in a University’ and then added ‘…I clean the lavatories.’

Of all the thankless tasks of an author, and there are many, writing a picture book is about the most thankless. If people think of picture books at all – which they mostly don’t – the only thought they have is ‘short’ and short means easy.

Even creative writing students think this. Many times when I lectured to undergraduates I’d set them a picture book writing task, and a little sly smile would spread over their faces as they imagined starting and finishing the assignment in ten minutes after the pub the day before they were due to deliver it. The perceptive ones learned by trying that short doesn’t equate with easy ( and the unperceptive ones delivered exactly the sort of texts you’d expect written with no thought in ten minutes. )

A picture book text is like doing very difficult yoga for your brain. In a 40 thousand word novel there a lot of places to hide. You can jolly your readers through a bit of plot that doesn’t absolutely hang together by keeping the pace up; you can distract them from one character that’s a bit two dimensional by making them root for another, better constructed one. You can even conceal your lack of ability to imagine a setting by focusing on the details in the foreground and keeping your dialogue snappy. But in a few hundred words – mine are long for picture books, about 600 or even 700 words – there is nowhere to hide. Even a misplaced full stop will trip the flow of the story. And the most important thing of all is motivation…it’s the most important thing in any story: the reason stuff happens; the reason characters do things. In a picture book the motivation for everything has to be absolutely solid, the link between every element in the text must be flawlessly forged.

And that’s really hard. In a nonfiction picture book where the narrative has a double job to do – working as a device to hold the reader’s attention AND as a device to carry information, it’s doubly difficult. You may think of a narrative element that works beautifully but it doesn’t add to the factual content that you’re supposed to be communicating. You may think of a gorgeous way to carry a fact but it won’t fit your narrative structure or voice.

Writing a non fiction picture book takes me AGES. I do the research…reading, searching the web, visiting libraries, museums, zoos, talking to scientists. Then comes the ordering of the information the sifting and deciding, and then the long, bleak search in what seems like a mental wilderness for the narrative thread…the coloured string made of voice and story that will string the beads of information into a pretty necklace. It can take weeks, months. By the time the 600 words of text is done I’ve tried every way to make it work and found what feels like the ONLY way. What I’ve done has been re written countless times . The whole thing is so carefully constructed that editing is especially painful. It can feel as if your editor is playing a particularly cruel game of jenga and has pulled the middle brick out your tower, making everything you’ve constructed teeter and crumble. I truly dread the editing process on these kinds of books. I have almost got over actually throwing up with worry when a text is delivered, and then crying when I get the feedback, but it took me a decade to handle the process more sensibly.

All the to-ing and fro-ing of editorial negotiation can even sometimes be political. When I chose to write a book about polar bears as a first person narrative told from the POV of a an Inuit I was told that was it politically incorrect and that I, as a white person, could not write as an indigenous Arctic native. I won the argument and had some very nice feedback from an Inuit hunter but winning it involved a lot more tears and upchucking.

When, finally all that is done, there comes the time to involve the illustrator. My dear beloved publishers Walker, do treat their authors with great respect so I get a big say in who illustrates my books. And I have pretty strong opinions about the look , the visual atmosphere that I’d like my texts to be given. We talk a lot about this before asking an illustrator if they’d like to be involved. Most of the time I get my first choices – illustrators like the text and the publishers, and they have a gap in their workload that fits the publication schedule. Sometimes I have a lot of interaction with the illustrator; we may meet and talk; I may send them reference material to get the information content of the pictures right or just to help with inspiration. And sometimes we never meet or speak. My text has to work its magic on their variety of creativity without any additional input from me, only from the editor and the designer.

When I began writing I found the necessary process of letting go involved in giving a text to an illustrator, very hard. Now I relish it and accept the collaborative nature of picture book making more and more. Only occasionally, when my words get pushed aside to accommodate artwork, does it hurt and feel I’ve been slapped down, back to lavatory cleaner status again.

When I began writing I found the necessary process of letting go involved in giving a text to an illustrator, very hard. Now I relish it and accept the collaborative nature of picture book making more and more. Only occasionally, when my words get pushed aside to accommodate artwork, does it hurt and feel I’ve been slapped down, back to lavatory cleaner status again.

So when I finally get the finished copies of a picture book in my hands, it represents a huge emotional journey. It’s like a chunk of autobiography in code, there for me to feel and remember as I run my fingers over the words I battled over and for, and marvel at the way they have been transformed by their marriage with the contents of someone else’s imagination.

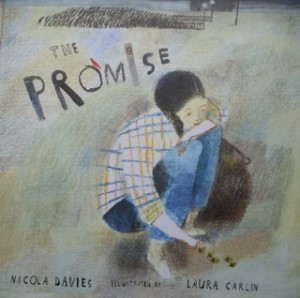

What I’ve described here – the struggle and angst and frankly, misery had been almost my only experience of writing picture books until I came to write The Promise. And that was very, very different.

My editor at Walker, Caroline Royds, whose judgement I trust completely, asked me if I’d like to write a picture book version of ‘The Man Who Planted Trees’. I knew the book really well and I re- read it. But decided I didn’t want to do a retelling, but something more my own and something that would be aimed at a human population that was now primarily urban. I think I also decided at that stage that I wanted to write a text that spoke across age groups. At the time my research for ‘Gaia Warriors’ my book about climate change, was still in my head: all the people involved in tree planting around the world; all the evidence of how trees in urban situations have a huge effect on local climate. But I was also in a pretty poor state my self; I was waiting for surgery on a shoulder injury and was in too much pain to think or work. Sitting at my desk for more than a couple of hours was impossible and I was seriously off with the fairies on strong painkilling drugs. So I couldn’t do the usual slogging. I couldn’t do anything in fact. So I did what I hardly ever do, I went on holiday. I lay in the late Autumn sun in the med for a week and didn’t even read. I didn’t even think, but I was aware that somewhere deep inside me, below the level where thoughts happen something was weaving and wefting and taking a shape.

I sat down at my desk on the Monday after I got back. I had no plan. No conscious thought. An empty head. I don’t remember really even what I did. But I know that two hours later I was on the phone to my editor asking if I could read her ‘The Promise’. Since that first reading we’ve taken out one line.

The decision about illustrator was just as organic. Laura Carlin was the only one. The moment I saw her work. Her understanding of space and how defining space defines emotion was astounding – clear and visionary; exactly what the Promise needed as it’s a story about the definition and transformation of space – physical and emotional. I think Laura’s journey to the illustration of the Promise was a bumpier one than mine in the final text. It’s not an easy text and I’ve often been told that my texts don’t leave enough creative space for illustrators. But Laura found her way, found her vision and created a visual world that gave my story a hinterland, a context, a new dimension. Laura’s work for The Promise turned out to be so much more than illustration. She plugged into that subconscious weaving and wefting from which the story was born and gave it a form. Her pictures for the Promise show how we feel about our bleak, urban, modern lives, they show the collective unconscious of how we long for the ability to change and transform ourselves and our surroundings.

The decision about illustrator was just as organic. Laura Carlin was the only one. The moment I saw her work. Her understanding of space and how defining space defines emotion was astounding – clear and visionary; exactly what the Promise needed as it’s a story about the definition and transformation of space – physical and emotional. I think Laura’s journey to the illustration of the Promise was a bumpier one than mine in the final text. It’s not an easy text and I’ve often been told that my texts don’t leave enough creative space for illustrators. But Laura found her way, found her vision and created a visual world that gave my story a hinterland, a context, a new dimension. Laura’s work for The Promise turned out to be so much more than illustration. She plugged into that subconscious weaving and wefting from which the story was born and gave it a form. Her pictures for the Promise show how we feel about our bleak, urban, modern lives, they show the collective unconscious of how we long for the ability to change and transform ourselves and our surroundings.

Every picture book I’ve ever done, even the ones that were the most painful to arrive at, I’m very proud of. Each one is the product of so much work and care and each one has an important job to do in the world…communicating information about the beauty and value of nature. But of all of them The Promise has the biggest job to do. The messages it carries are so simple, so universal: that we can transform ourselves and transform the world; that change is possible through a reconnection with the natural systems from which our long story has arisen; that a bad beginning doesn’t mean a bad end. But these messages are hugely important, timely and if taken right to the heart, utterly revelatory.

Ever since I began to write more than 20 years ago, I always said I would rather write a great picture book than win the Booker. With the Promise I feel I’ve achieved that ambition. Or rather that ambition has been achieved by the magical interaction of various elements: a strange, alchemical process in me, which I don’t understand and can’t take credit for; by the genius of vision and spirit in Laura Carlin; by the nurture and care of our editors Caroline Royds and Liz Wood. It is this magical interactive collaboration that makes pictures books such an extraordinary and important art form, deserving of far more attention than they get from adult reviewers and media commentators. It makes them quite different from anything else in publishing or the world of visual art, where creativity is most often the expression of inward looking ego. It is what makes them as powerful as silver bullets, carrying messages right to the centre of our emotions and the deepest currents of our psyche. It is what makes the thankless task of writing them uplifting, humbling, humanising and what I want to spend my life doing.

And a small POST SCRIPT….

Since writing The Promise I’ve had one other experience of a picture book text writing itself. It’s another story, that will have to wait a little to be told fully, but it’s called The King Of The Sky. Mark Hearld is illustrating it and it will have a life as a performance with Karine Polwart’s music – but when and how I’m not yet sure.