A dream landscape fills the space between me and the horizon; layer upon layer of green, tree-clothed hills whose shapes could have been crafted by a movie director seeking to represent paradise. It’s almost too lovely to be true, and yet it’s real. This is Khe Nuoc Trong 20,000 hectares of lowland rainforest in the Annamite Mountains of N central Vietnam. Somewhere in those hills rare creatures with names that sound like magic spells- white cheeked gibbon,, saola, sunda pangolin and red shanked douc, hatinh langur.Somewhere.

I know I won’t see the shy herbivores or the pangolin, but I’m hoping for primates – especially red shanked douc and gibbons. In fact, I’m more than hoping, I’m not feeling like the very grown up World Land Trust Trustee I’m supposed to be, and more like an excited six year old before a birthday party – GIBBONS SINGING!!!! RED SHANKED DOUC!!!!! YAYYY!!

Right now though, there are immediate realities to deal with: the heat and the weight of my back pack; the plastic sandals over leech socks, I’m advised to wear. It’s like walking with a pair of cloth shopping bags on your feet. Seeing my dubious expression Viet Nature director Pham Tuan Anh explains that these are the shoes in which the Vietnamese army defeated the might of the US. They are, she says, very good for river crossings, and we’ll be doing a lot of those.

Khe Nuoc Trong is laced with waterways, and is a ‘Watershed Protection Forest’, its purpose to safeguard those clean waters. As such, it receives a measure of legal protection; the extraction of some forest products is allowed, but hunting and logging are, in theory, illegal. However, the evidence of exploitation of the forest are easy to see beside the trails we follow -the tracks and dung of water buffalo and the ruts left by the logs they’ve been used to haul out.

village shops are a lifeline for locals but they are also a route for the sale of bush meat and other forest products

As we walk along increasingly steep and narrow paths, the signs of human use recede a little. The rubber and acacia plantation are replaced by disturbed, but more diverse forest, which begins to show signs of animal life; cicadas chirr and, along a stream bed, there are frogs calling invisibly from right under my every footfall. It’s a very odd and particular sound, that of a muzzled chihuahua barking in a box in a tiled bathroom. As no one knows what the frogs are actually called, I name them the ‘chihuahua box frogs’.

After an hour and a half of walking we reach a forest ranger station, not much more than a garden shed with hammocks, on a wide bend of the river, where two forest rangers are stationed. A structure that looks like a failed attempt at a bridge marches the width of the water, “It stops people floating logs downstream.” Tuan Anh explains.

bridge like structure prevents loggers floating their cache downstream (there were masses of diddy tadpoles in the shallows and loads of fish)

Viet Nature works closely with the Forest Rangers providing them with training and equipment to help move biodiversity up the agenda of the Forest Protection Service.

“We work with local people too, “ Tuan Anh explains “to encourage them to use the forest in more sustainable ways.” This means education and providing villagers with ways to make a living that don’t hurt the forest, such donating 4000 fruit trees to grow and crop in and around settlements, and rattan plants to grow on the margins of the forest and provide a lucrative and sustainable forest crop. Gradually, local people are learning more about Viet Nature’s work and are increasingly supportive and proud of the diversity of their forest.

We follow a path along the river and the opposite bank rises in a smooth, green curve. It looks gibbony to me, but my excitement will have to go on hold for the time being: there are patches of scrub where trees have been felled and gibbons need unbroken canopy to swing through. Red shanked douc too are very discerning and like undisturbed forest, designated as ‘rich’. In spite of its promising look to my eye Viet Nature co founder Le Trong Trai (Mr Trai) tells me it is the lowest of the three categories of rainforest, ’poor’. Definitely not fit for gibbons.

By sunset we are four hours walk from human settlement, and yet the forest here is still obviously under pressure. There are still signs of buffalos and humans, occasional tracks and sweet wrappers, and Mr Trai tells me its only of ‘medium’ diversity. All the same, it is beautiful; I notice there are a lot more chhuauhua box frogs and I count five different kinds of butterflies in combinations of orange, sky blue, neon green, patrolling the river banks.

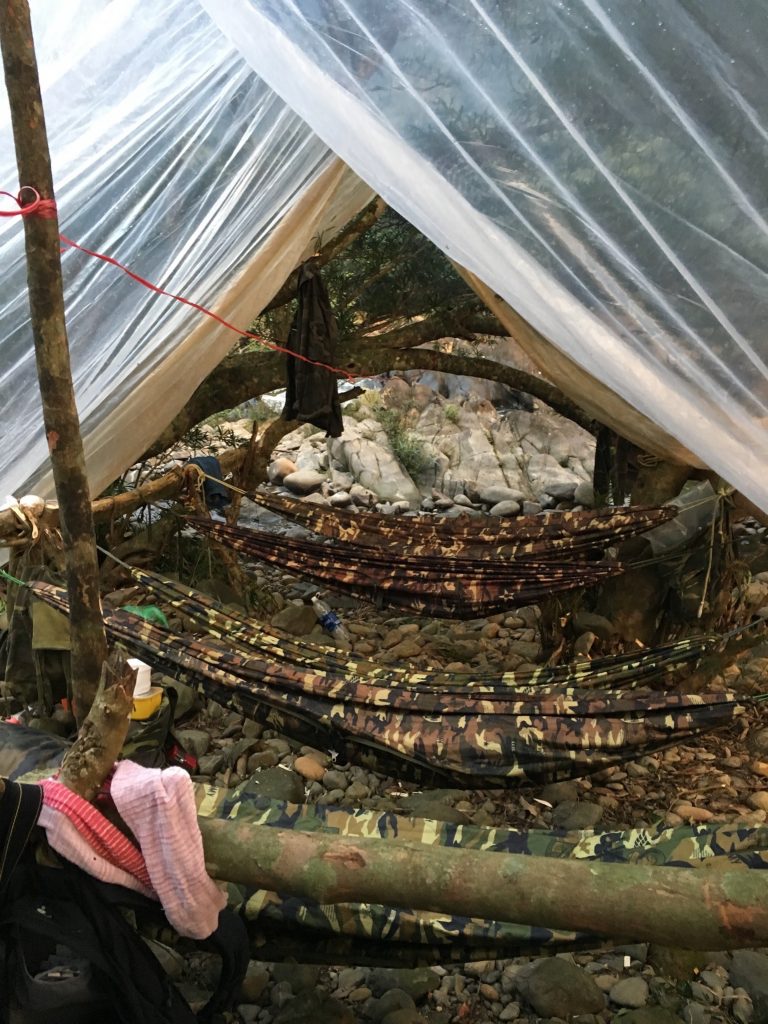

Viet Nature rangers Tran Dang Hieu, Le Van Ninh and Le Cong Tinh make a perfect camp from branches and polythene sheeting, beside another ravishing river bend.

They cook a wonderful meal, a ‘phoo’ of chicken, and vegetables from Ninh’s garden.

so many insects flew into the lamp light, I’ve promised Tuan Anh to come back with a mouth trap next time

They chat and laugh in the firelight and I’m filled with admiration for these young people, who live for weeks on end deep in the forest, two or three days walk from the nearest track, separated from their families. Their tireless work, setting up camera traps, scientific monitoring and keeping track of human activity in the forest is the backbone of Viet Nature’s work in Khe Nuoc Trong and has helped to prove the presence of a treasure trove of endangered and rare species. Tuan Anh has the camera trap footage on her computer and, balanced on round rocks for stools, she shows me one delight after another but my favourites are an annamite striped rabbit, like Peter Rabbit in prison fatigues, and a fantastically busy Asian short clawed otter, which seems to be searching for a river under the leaf litter.

“We’re adding new species to our list all the time.” Tuan Anh tells me with a big smile.

We sleep in hammocks – ex US army I’m told gleefully – with in built mosquito nets. It’s like being a caterpillar in a cocoon; I sleep like a baby.

In the morning we continue our journey in to the forest. It’s magical: frog and butterfly counts rise steadily with every river crossing. Mr Trai keeps a up a quiet labelling of every new bird sound we hear, some like aural newsprint, some like poured gold ‘Red vented barbett, laughing thrush,’. I stop keeping a tally of the river crossings and simply enjoy the moments of coolness.

At last, we are standing on the edge of Viet Nature’s reserve: 768 Ha leased from the government, who own the whole of Khe nuoc Trong, and designated for scientific research. No logging or hunting are allowed here, and even in the short time since their lease period began, the impact is obvious, with fewer signs of human encroachment and a measurable rise in species diversity. It is Viet Nature’s plan to manage the whole of Khe Nuoc Trong’s 20,000 ha in this way and their proposal to designate the whole of forest as a nature reserve is supposed by the provincial government

At last Mr Trai looks happy. ‘This ’ he says with a beaming smile, is ‘rich’ forest.

from left one of the forest rangers, Tran Dong Hieu,Pham Tuan Anh, Tran Van Hung, Le Trong Trai (Mr Trai) on the edge of ‘rich’ forest

It certainly seems very different from the forest where we began our journey – no two trees are the same, the canopy is closed and the whole feel of the place is more alive but its hard to get a picture of a forest as a forest, when you really can’t see the wood for the trees. So, it’s not until the next day that I get a real sense off the scale and diversity that Khe Nuoc Trong holds and why its so important that Viet Nature get their wish of managing the whole area as a nature reserve.

At five am, I stand on the great, concrete highway that slices through Khe Nuoc Trong. Behind me is the 768ha of the Viet Nature reserve and the disturbed forest surrounding the farms and villages that encircle it. In front, layer upon layer of almost untouched rainforest stretching from here and over the border into Laos. As the sun comes up and replaces the splashed, silver moonlight, its diversity is immediately apparent. The variety of tree shapes and colours takes my breath away. So far, Viet Nature has counted 1500 different tree species in Khe Nuoc Trong – more than in the whole of North America. There are no holes in the canopy here, this is gibbon country and my excitement levels are once again off the scale.

Le Van Ninh, the resident gibbon expert, who has surveyed these forests and found 300 families of gibbons, whizzes up the road towards me on a motorbike. His beaming smile is enough to tell me what he’s found, so I jump on the back and we fly down the highway into the green dawn. This road may have sliced the forest in two, but it has allowed tourists to appreciate its wonders from the back of a bike. More come every year and contribute to the economy, enhancing the value of unspoilt forest to local communities, who can augment their income by providing facilities for tourists.

Right now though, I’m simply in heaven because I can hear gibbons calling. A male’s lonesome wail floats over the mist that gives away the path of the river, somewhere under the green, and is answered by another call from up the valley. Ninh points out the position of three gibbon families in the valley and hills before me. A female joins her mate, whoop, whoop, whooping. I imagine them sitting, side by side on a branch, letting their voices reach out over the tree tops, sharing this moment together, like a human couple with their morning coffees. What do they see? What do they feel these little apes, our cousins?

No time for more philosophical speculation, because the rest of the Viet Nature team are here and there are furious bursts of Vietnamese and lots of pointing: two hundred meters away, right beside the highway, a little party of red shanked douc are making their way through the trees. The views I get are brief, just glimpses really; those pale geisha faces with their almond eyes and frame of lemon curd fur, the flash of the white tails and the flare of the red ‘shanks’. But those micro moments gleam in my eye, and are instantly imprinted on my heart forever.

At that moment, with the gibbon voices still in my ears and the red shanked douc faces still in my eyes, the forest seems endless, but later that day I see how truly vulnerable it is. We cross into the next province and see the forest end shockingly abruptly.

Trees and trees and then, bare hillside. Nothing. Fifteen hundred tree species, frogs, birds, insects, monkeys, gibbons, pangolins simply gone. As if they had never existed. Of course I know this happens all over the world, but to see it is incredibly shocking. Some of the destruction is old, the result of agent orange in the war, but some of it is new: rural poverty drives people to clear forest to grow crops or graze animals, even though they know that the soil will not support more than a few seasons of productivity.

Viet Nature, their scientists, their conservationists, their rangers, are all that stand between the voices of gibbons, the quiet twirling of pangolin tails, the almond eyes of monkeys and these barren hillsides, with no clear flowing water, with no deep locked store of carbon and without a fat slice of the worlds most precious treasure, biodiversity.

on some forest trails its possible to get about on motorbikes Viet Nature rangers could give Barry Sheen a run for his money

A seven year old once asked me ‘where is the rainforest?’ in the same way she might have asked’ where is Narnia?’ The idea of ‘the rainforest’ has entered into our collective psyche and it does a powerful and important job there, keeping alive the magic and wonder of the big wild. But we must always remind ourselves, and others, that the rainforest is not one thing, it is many real forests around the globe, each with their own particular mixture of species, each infinitely precious, and in need of the very realest kind of protection we can give them.

SUPPORT THE WORK OF THE WORLD LAND TRUST , VIET NATURE AND OTHER ORGANISATIONS AROUND THE WORLD