Last night I watched an amazing documentary, ‘A World Without Down’s Syndrome?‘on BBC iplayer, made by the actor Sally Phillips. It was about her experience of having her son Ollie, who has Down’s Syndrome. I’d recommend that you watch it, if only to see the opening sequence of Sally (who is the sort of person you instantly wish was your best mate) having a water fight with Ollie and his two brothers, who are all just gorgeous boys.

But it wasn’t a sanitised feel-good film saying that ‘every family should have a disabled child, it’s lovely.’ It raised some really difficult questions about choice, and if it’s always a good thing: do we really have the insight and intelligence necessary to make choices that modern medical technology allows us to make? Do we even have the right information to make those choices?

When I was pregnant – a very, very long time ago – I had the standard test to see how likely it was that I was carrying a child with  Down’s Syndrome. I clearly remember the dread with which I waited for those results. I don’t know how I would have reacted to a result that said I was carrying a disabled baby; I’m pretty certain I would have had a termination. But what would that choice have been based on?

Down’s Syndrome. I clearly remember the dread with which I waited for those results. I don’t know how I would have reacted to a result that said I was carrying a disabled baby; I’m pretty certain I would have had a termination. But what would that choice have been based on?

Firstly this: seeing Down’s syndrome adults on an outing in a local cafe when I was 10, and picking up the horror and disgust expressed by the other patrons. The default setting of our society is that disability of any kind should be seen and not heard, locked away where we ‘normal’ people shouldn’t have to look at it. The big message that society gave then, and still gives now, is that disability is just not OK. And of course that’s a vicious circle. The less visible people with disability become, the less we experience them as PEOPLE, the more we feel them to be OTHER. And who wants their child to be part of that gang?

And secondly, this: I was a working mum. Terrified, at the time, that the children that I truly, desperately wanted, would impede my progression up the career ladder. Working as TV presenter, as I was back then, required me to tell the world that I could give birth and go straight back to work. Just about possible, I felt, with a ‘normal’ baby, but what about a disabled one? I feared the unknown, and with no experience of seeing mothers with disabled kids, my ignorance coloured that space black.

Since then, I’ve had more contact with families and children living with disabilities. I’ve seen kids with miserable cocktails of multiple  impairments, who really are having no fun, and their poor ragged, exhausted families who aren’t either. And I’ve seen kids with disabilities who have lit up and glued together their domestic situations and become the irreplaceable stars of their family universes. And many shades in between.( look at this wonderful book Hole in the Heart Bringing up Beth by Henny Beaumont)

impairments, who really are having no fun, and their poor ragged, exhausted families who aren’t either. And I’ve seen kids with disabilities who have lit up and glued together their domestic situations and become the irreplaceable stars of their family universes. And many shades in between.( look at this wonderful book Hole in the Heart Bringing up Beth by Henny Beaumont)

The problem is, that, because of our inability, as a society, to talk about any of this openly, our perception of disability is always entirely negative. Sally’s excellent argument was, that as medical science gets better and better at predicting what

a foetus will be like, we will weed out more and more babies with any kind of disability. And then any kind of feature we don’t want – a big nose, the wrong colour eyes, a predilection for mental instability.

As a biologist I think this is risky territory. Over the next 300 years life is going to be pretty tricky as we sort out our relationship with our parent planet – who know what genes that lie hidden in the tangle of our DNA might get us out of a hole? So it seems crazy to be pruning our population to an ever narrower vision of what is normal, beautiful, sane and well.

As a human I feel that the notion that we can control our lives and what happens in them is pretty illusory. The unexpected, the unpredicted, the serendipitous is the grit in the oyster of our lives, that can cover us in pearl dust even as it cuts our flesh.

The modern world with its requirements to rush, achieve, get, get, get, leaves little space for caring, for spending a morning making sandcastles or holding someone’s hand. It is this society of ‘getting and spending’ as Auden said, that ‘lays waste our powers’, our powers as loving, insightful humans, growing from the day we are born to the day we die. It requires us to edit out of the world all that is in the way of things and stuff – people who need help, people who need care, people who don’t give a damn about poggenpol kitchens and ipods. These are the very people who might just remind us of what really matters.

So should we give up testing our unborn children? I can’t answer that. I am lucky, my kids are fine and well (touch wood). But we should certainly talk about all this and stop shutting disabled people behind doors, as if they were not part of the human race.

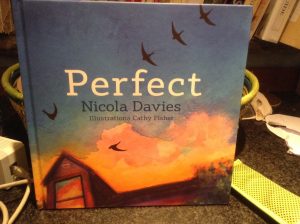

And here is a footnote: a really lovely thing happened this week in connection with all this. This year my story ‘Perfect’ illustrated by Cathy Fisher was published. I’ve written about this elsewhere, ( and here too) but it concerns the birth of a disabled child. Every big publisher  turned it down, including those with whom I have a long track record. It was finally taken by a wonderful small (but growing) publisher here in Wales, Graffeg Books . It is now available in America and, in November,will be getting a stared reviewed in Kirkus Reviews (V V big deal for kids books in the States):

turned it down, including those with whom I have a long track record. It was finally taken by a wonderful small (but growing) publisher here in Wales, Graffeg Books . It is now available in America and, in November,will be getting a stared reviewed in Kirkus Reviews (V V big deal for kids books in the States):

‘A fledgling swift helps a child cope with disappointment when a baby sister is different than expected. The swifts return the same day the baby comes home from the hospital. The white narrator watches from the window, imagining “racing and chasing” with the baby. But something is wrong; dark, looping scrawls suddenly mar Fisher’s eloquent, luminous pastel compositions. The baby is too still. (The baby’s condition and prognosis are unknown; the baby herself is often shrouded in mist.) The birds circle as the pensive child plays alone and confesses, “I didn’t want to feel the way I felt. But I couldn’t love my sister, no matter how I tried.” But after the child helps an injured fledgling to fly, the child wonders if the baby likewise “only needs a little help.” A close-up of the fledgling’s sharp-eyed face is mirrored by a close-up of the baby’s white, frail face—the baby’s dark eyes are sunken but gaze at readers with a similarly knowing expression. As the siblings lie in the garden, the narrator declares how it will be: the two of them, “screaming with delight and laughter.” Davies deftly addresses—and respects—a dark feeling, and though her optimistic symbolism will certainly reassure children, it will equally reassure parents struggling with their own uncertainty or grief. An emotionally vivid, hopeful illustration of unpredictability, disappointment, and acceptance—recommended for children and parents alike. (Picture book. 4 & up)’

This reviewer seemed to completely get what we were trying to do with the book.I’m not saying any more, but you can join the dots; hopefully our book will open up some much needed conversation about all of this.