More than a decade ago, actually a lot more than a decade, I went to Ireland on holiday. The aim was mostly to wander about the Burren and look at gentians, but somehow I found myself in Birr, a lovely little town in county Offaly. We, my then partner and I, wandered into the Park of a great house, Birr Castle without knowing the first thing about the place, and found a giant telescope, built in the 1840’s by the Fourth Earl of Rosse.

The story of the Telescope – the Leviathan Of Parsonstown as it was known – got into my blood. I returned to Birr, where the current Earl and his wife were totally welcoming and helpful. I was given access to the family archives in their library and spent several days poring over letters and texts, swimming in long gone lives. I came home and over one, mad weekend wrote 10 thousand word proposal for a US publisher. It was intoxicating to be so possessed by a story of a kind I’d never thought about before.

For a while it looked as though the idea for the book had sold for enough money to actually allow me to write and research it. But, as is the way with publishing, the enticing bubble burst. Yes, I could still write it, yes, it would probably be published, but no there was not an advance that would allow me to pay my mortgage and keep my kids fed and clothed.

I admit, I gave up. I had other things to write, students to teach, kids to worry over and life at the time was generally rather an uphill struggle. The story got carried from computer to computer, even though the files would no longer open. But it haunted me. Every time I heard of some event or person in public life in the 1840’s I found myself thinking did my Earl know about this?

Now, I have reopened the file and the story is buzzing in me again. So dear reader, if you have a little time, read on….

In the Leviathan’s Eye

The story of the Great Telescope at Birr

by

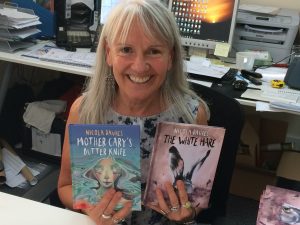

Nicola Davies

The Romance of the Leviathan

WHAT MAKES A ROMANCE? A real, old style Romance? A story with substance and drama, fantastical perhaps, but holding before us a vision of human glory that illuminates and enobles the small truths of our own lives. The ingredients of this sort of Romance are part of our collective unconscious, the emotional landscape that lies in the realm of our dreams, in the undercurrents of our lives that flow deeper than words.

A hero and a heroine are the first ingredients. The hero need not be handsome, but he must be bold, resolute and determined, undeterred by any variety of adversity. He may be misguided, he may be misled, but his moral stature is never in doubt. His heroine must be beautiful, but simple physical beauty is not sufficient. She must be wise, strong, faithful. She must above all endure — all separations, all griefs — with a pure spirit and a loving heart.

There must of course be a quest. It should be noble and it must be selfless. It need not be successful, in fact ill fated or even hopeless quests display the moral quality of the hero and the endurance of the heroine to best effect.

There has to be tragedy — death after all is the ultimate definer of human stories. And there should be a Magical Object, imbued with power and significance.

There are few myths or great fictions, fewer still stories drawn from real lives, that manage to gather together all these ingredients, but the true story of the Birr Castle telescope, the Leviathan of Parsonstown, has every one.

THE HERO: William Parsons, the Third Earl Of Rosse. Astronomer and engineer. Portly, plain and shy but acutely intelligent, almost pathologically determined, and unfailingly kind.

THE HEROINE: Mary Wilmer Field, Third Countess of Rosse. A noted beauty and a pioneering photographer, with a gold heart within an iron will.

THE QUEST: To build the world’s largest astronomical telescope, the Leviathan of Parsonstown. This giant would look deeper into the universe than had ever been possible before and reveal the almost unimaginable depths of time. It was a quest that was both gloriously successful, and fatally flawed.

THE TRAGEDY: William and Mary were shaped by it. John Parsons, William’s dearest brother, died on the threshold of life at twenty six and Mary’s mother died in childbirth, when Mary was small. All their lives grief was a companion for both our hero and heroine, as they lost seven of their eleven children before adulthood.

THE MAGICAL OBJECT: the Leviathan itself, and most particularly the vast metal mirror (four tons of bronze) that was its eye onto infinity. When polished bright, the eye’s vision was unsurpassed, but when tarnished it was almost blind, calling down scorn upon the Leviathan’s reputation, and tainting William’s quest with failure.

THE SETTING: William’s beautiful Castle, Birr, County Offaly, now in Eire, at the time of the potato famine that killed a million people and exiled a million and a half more; British Society at a time of social unrest and on the verge of overturning the Universe created by God.

The Leviathan Of Parsonstown … once upon a time in Ireland

On the edge of Parsonstown, a little farming settlement in Southern Ireland, on the very eve of the potato famine, a window onto the depths of space and time was opened: The vast spirals of other galaxies, separate from our own, became visible for the first time, and the immensity of the Universe gaped wide under human gaze.

This window was a new telescope, a giant reflector, with a mirror six feet across, mounted in a barrel fifty eight feet long. It was the biggest telescope that had ever been made and, soon after its official opening in 1845, was nicknamed affectionately by the local people ‘The Leviathan of Parsonstown’. The observations it made were ground breaking, and were only bettered by modern telescopes and photo astronomy in the 1950s. Its huge mirror, like a giant eye, could see what other smaller telescopes could not: That some nebulae – bright amorphous patches in the sky – were made of stars, drawn into spirals and discs as if by some invisible cosmic whirlpool. It saw that our galaxy was not alone, that there were many others populating infinity.

The ‘Leviathan’s’ creator was William Parsons, Third Earl of Rosse, an engineer and astronomer with a determined taste for problem solving. He built a world-beating astronomical instrument, using only those resources available to him in the surrounding countryside: Peat from the bogs fired the forges to smelt the alloys for the telescope’s mirrors; coopers adapted their expertise to work on the large scale of the monster barrel; the minds, hearts and hands of local workmen were fired by William’s enthusiasm to learn new skills, and to become a part of the Great Telescope project. William was no revolutionary Irish nationalist, but he did have a quiet belief in the independent potential of the Irish Nation that the making of the Leviathan eloquently demonstrated.

William Parson’s home, the seat of the Earls of Rosse, was Birr Castle. It still stands on the edge of Parsonstown, now known by its original name of Birr. Birr has been a settlement since seven hundred years before the birth of Christ. Its name derives from the Irish word meaning ‘abounding in wells’, or from ‘biolair’, the word for watercress, a favourite food of St Brendan. Whatever the precise meaning, Birr has a watery connection fixed in its name from the rivers Camcor and Little Brosna, that flow though it and around it. Nowadays the Camcor skirts the town centre. On hot days you can stand on the little bridge opposite the Catholic church and watch the trout flapping their tails lazily against the speckled bottom. Small children shriek as they splash in the cold water in their vests and pants, and old ladies in support tights and cardigans natter on the park benches there. The Camcor winds round the back of the new Technology Centre and the Tourist Information Office, past the old Maltings, now a smart hotel, and into the grounds of the Castle, right below the beautiful gothic windows of the music room built by the Second Earl. It continues into the Demesne where it joins the another stream, the Little Brosna. Both rivers still seem clean enough to provide the best watercress for any passing Saint.

The main part of the town centre is roughly Georgian, built mostly in William’s father’s and grandfather’s time. The streets are wide with tall shop fronts painted in bright colours. It has that relaxed but vital feel you get in all Irish towns, unselfconsciousness about mixing past and present. Half way down the main street there are two 50s petrol pumps, quite disused, standing opposite a shop that’s pandering to the latest craze for body tanning products. There are chic glass payphone booths with instructions in several languages, and a deli advertising sun dried tomato bread. There’s a great to-ing and fro-ing of young people in the Square this evening (it’s suddenly clear to me why Birr supports five hairdressers). But the place where they’re all going to to ‘hang out’ is Dooley’s Hotel, which looks the same now as it did a hundred and fifty years ago. Birr seems to be thriving, but it still has its individuality. It has a definitely rural feel, so that on a warm June evening, swallows swoop down the main street, rather than the more urban swifts, and jackdaws converse on the rooftops. There’s a quiet, too, behind the bustle of passing cars and giggling adolescents. It’s the quiet from the lush, even landscape all around the town, with the hay new cut in blue-green rows, and the barley ripening, just the way it has for centuries. The local news on the radio trickles out of an open window, including a full five minutes of farming reports on the state of cereal crops. The advice to check for aphids and spray your wheat in time for harvest is entirely modern, but the place of agriculture in the lives of the people of Birr isn’t, it’s as central now as it was in William’s time.

That sense of integration extends to the relationship between the Castle and the town. There’s no separating acreage of park land between the Parsons and their community. It’s true that Birr Castle is behind a huge stone wall, but only just behind it, and the wall itself stands unceremoniously at the top of the streets on one side of town. Sitting with a drink outside Kelly’s Bar, I can see the upstairs windows of the Castle, at the other end of the street, with some rather ordinary-looking curtains blowing in the breeze. The wall is no more of a barrier between Baronets and commoners than the sort of high fence a shy neighbour might erect: You can still see his face at the window and hear if he swears at the cat.

Both Laurence, William’s father and William himself could have changed the location of the Castle and built new accommodation further into the Demesne, away from the town. They could so easily have lived elsewhere — other Irish nobles did — as the family had property in Dublin and in London. But Laurence, the Second Earl, was scathing about absentee landlords who took from their tenants and communities but gave nothing back, as he shows in this poem ‘The Absentees’ which he wrote in 1801, when William was a year old,

Nobles when your country you thus forsake

Say what return is made for what you take?

For inequality what’s the defence?

The evil glance? But what’s the recompense?

Shall you the pillars of the realm at home

Mere useless emigrants in England roam?

Shall you live idly there from year to year

Designed for noblest duties here?

All things derive their value from their place

Position constitutes their use and grace

The smallest atom that compounds a fly

Is not misplaced without an injury

— Laurence Parsons, Second Earl of Rosse

Laurence’s commitment to Birr wasn’t only a matter of personal morality, it was a statement of political belief too. Laurence was a friend of Irish Nationalist, Wolfe Tone, who committed suicide whilst in a Dublin gaol on a charge of treason, after the Irish Rebellion in 1798. Tone wanted to replace the separate identities of his countrymen as ‘Protestant’ or ‘Catholic’, with the common identity of ‘Irishman’. Laurence didn’t share Tone’s revolutionary beliefs, he certainly didn’t hold with democracy and universal suffrage, but he did believe in land. Land ownership was important, and landowners should be allowed to decide how the land as a whole was run. That meant the right to vote and to take political office for landowners, no matter what their religious affiliations. Although the Parsons were Protestant, Laurence attempted to treat both Catholics and Protestant alike. It was a tricky line to walk and he risked suspicion from both sides. In post rebellion Ireland, Independence had become a Catholic creed, and Protestants were expected to to support the Government in England. All the same Laurence determined to bring William up in accordance with what he believed. So William’s first public duty, as the heir to the Demesne, was to lay the foundation stone of the new Catholic church in Birr, when he was just seventeen.

Laurence strongly opposed the Act of Union which abolished the Irish Parliament. He left the Commons in disgust when it was passed in 1801. But that was the year after William was born, and perhaps Laurence’s decision was motivated partly by a desire to be at home more often than sitting in the English Commons would allow. In any case, he detested being in London, and whenever he was there couldn’t wait to be home,

‘..my cage will soon be open and I will not delay a moment in taking advantage of it…’

Laurence wrote from London on a visit to the Lords in 1805.

Whatever Laurence’s disenchantment with politics, William entered the English Parliament representing an Irish Constituency, when he was just twenty three. Laurence’s convictions seemed to have rubbed off on William, who was a Whig not a Tory, and supported the Irish Emancipation Bill, that gave political representation back to Irish Catholics. Like his father he didn’t stay in politics. When the choice came between astronomy and the Commons, he voted with his feet and left, keeping only his seat in the Lords.

Although both William and his father had strongly held convictions about Ireland, they were neither of them career politicians. Ultimately it was more important for them to be home, at Birr. For both father and son, being a part of Birr was the backbone of their lives and lay at the core of who they felt themselves to be.

*

The street lights of Birr town leak a little over the walls of the Castle but still the Demesne is very dark at night. The lake that William had made shows its place only by the faintest glassy glitter, and the parkland of meadow, trees and gardens that draws the attention by day, lies low in the shadows. Look down and there’s nothing but featureless dark, but look up and the sky is suddenly big. A vast stage of limitless possibility, arching from the battlements of the Castle to an horizon that seems a thousand miles away.

William spent almost all the nights of his childhood under this sky, at Birr. He was never sent away to an English public school, as the children of the Irish nobility usually were. Laurence and his wife Alice wanted their children at home and engaged tutors to educate William and his younger brother John. So there would have been plenty of opportunity for William to look at the stars and wonder.

Astronomy was creating quite a stir in intellectual circles of the late eighteenth and early nineteenth century. Observatories at Armagh and Dublin were established in the last decades of the eighteenth century and were increasingly active in the first decades of the nineteenth. As a prominent public figure and a man of considerable intellect, Laurence would have been aware of developments in all cultural spheres and would have shared what he could with his growing sons. As William got old enough to accompany Laurence on trips to London he was exposed to the scientific life of the times. . He joined a number of newly established Societies — the Royal Horticultural Society, the Geological Society among them. But the most significant was his membership of the The Royal Astronomical Society, begun when he was twenty four and the Society itself was just four years old.

The star of the stars at that time was William Herschel, a career musician turned astronomer and telescope maker. Herschel, together with his sister Caroline, were at work and making exciting discoveries: binary stars, new comets, infrared radiation, moons of Saturn and of Uranus (the planet Herschel had himself discovered). The telescope that Herschel completed in 1780 was the largest so far, with a forty nine inch diameter mirror and a forty foot barrel. With it he began to examine ‘nebulae’, mysterious blurs of light, like clouds of glowing mist in the sky. These nebulae, he felt, were all part of the evolutionary processes that gave rise to new stars and planets. With so many nebulae visible to his new telescope, Herschel felt that all the stages in the birth of solar systems taking place over vast eons of time, could be viewed in the tiny span of a human life. Herschel’s theories were added to by a French astronomer, Laplace whose wonderfully titled paper ‘The System of the World’, published in 1796, stated that nebula must spin slowly over time to form planets from the the eddies of that spin, and stars from the central core.

It was all very exciting in a world which was beginning to suspect that God might not have created everything four thousand years ago last Monday. And it was all happening right above William’s head in the dark over County Offaly. Up there new worlds were forming, stars and planets being born. All William had to do to see it all, was find a way to look. It must have made the night sky seem full of the possibility of adventure and discovery.

William certainly had the right natural talents for astronomy. Both William and John were very bright boys, with a special aptitude for mathematics which they drew from their mother, Alice. John, though two years younger than William, kept up with William in his studies every step of the way. They both went up to Trinity College Dublin to study and then very soon transferred to Magdalen College Oxford, graduating with first class honours in mathematics in the same year.

There was a practical side to the boys’ intelligence too. Laurence was a skilled architect and amateur engineer, and the boys had grown up watching their father design and have built innovative extensions to the Castle. At about the time they both came down from Oxford an extraordinary suspension bridge was built over the river Camcor beside the Castle. It is like a spider web of white painted wire, stretched elegantly between stone pillars. It is perhaps two feet wide and twenty long. You can still cross it, one at a time and carefully (I did so in bare feet) and stand over the river below, looking up at the most ravishing aspect of the Castle. To an untrained eye it seems merely magical, but to historians of architecture and engineering it is a place of pilgrimage. It was the first of its kind in Ireland and predated Brunel’s work in England. Did Laurence set the new graduates a practical challenge to test their mathematical and engineering skills? ‘Build me a bridge boys, let’s see if your mathematics is useful for anything!’ All the circumstantial evidence suggests that he did, and that the bridge is there to show that the boys rose to meet their father’s challenge in great style.

The scientific climate of the time primed William to astronomy and his education and natural talents trained him for it. But from where did William draw his passion for looking further and further into the eye of infinity? It seems very likely that it was at least in part, from the work of William Herschel, and in particular one of the last papers he read to the Royal Society in 1817.

William was a serious student of Mathematics by then, and as such he would certainly have read Herschel’s papers. In 1817 Herschel was 78 years old and unlikely to be giving many more public appearances. William was making regular visits to London with his father by that stage, and attendance at Royal Society Lectures was a standard of Laurence’s London itinerary. Would William have missed the chance to see the great man Herschel, and hear his new theories? Very likely not.

This latest paper was extraordinary, it attempted to measure the depths, the great unimaginable depths, of space. Herschel at first pointed out the fact, well known to astronomers of the time, that the brightness of a star is inversely proportional to its distance from the viewer. So, a star will be four times as bright as a similar star that is twice as far away. By meticulously comparing the brightness of stars with a standard bright star (Arcturus in the constellation Bootes) Herschel mapped the relative distances from Earth of a sample of stars in all parts of the sky. He called this measure Profundity. He measured stars with the smaller of his telescopes that were up to the nine hundredth order of Profundity away, and postulated that with his bigger telescope (which he hadn’t used for this) he would see stars that were of the two thousand three hundredth order of distance from Earth. Using his measurements he was able to make a rough map of our position amongst the stars in our part of the Milky Way, but wasn’t able to see to the end of it and in some directions the mass of stars at great distance was just a blur of light, too far away to distinguish one from another.

The ‘map’ was really the roughest of diagrams and Herschel was disappointed that it wasn’t better. In addition he knew that his method was flawed as it relied on stars being of a single standard luminosity. In fact, that property can vary by ten thousand fold (although as a very rough measure of distance Herschel’s method is still used by amateur astronomers today).

In spite of the problems inherent in the paper, it communicated something important to the youthful William. First, that space was very big indeed. If Herschel had seen to the two thousand three hundredth order of distance and that still wasn’t the end, then what might there be out there to be discovered? Second, that with a telescope bigger than Hercshel’s forty nine inch reflector, it might be possible to see what lay out there, beyond the Milky Way; to resolve the blurry mass of far off stars, the shapes of the faintest and most distant of nebulae, into constellations, planets, worlds. Out of the memories of stary nights at Birr, of the web of astronomical formulae he had read, of the dawning aspirations of a young heart, William’s life-long love of infinity was born, like stars condensing from a cloud of glowing dust.

Although William was the heir, John was considered to be the brightest, and great things were expected of him. When William entered Parliament in 1824 John went to London too, to continue his studies in law. Their letters home show their contrasting personalities and the teasing and rivalry, usual between brothers:

‘William has caught a slight cold’ reports John from London in 1826,

‘I believe by walking at a rapid rate while he is thinking of political economy, getting into a heat and then loitering.’

And a few days later John is openly ‘telling tales’,

‘William’s cold is much better, he has not however resumed his attendance at the House.’

John’s letters are warm and chatty, full of gossip,

‘Boscha is accused of bigamy. However he thinks himself in no danger as his first marriage took place in France …’

and details of parties,

‘… cakes, blancmange, jelly, fruit tarts, lemonade, wine etc with a few cold cuts. William had an invitation, but of course did not go!’

William’s letters are much more sober, full of political questions for his father and big brotherly concern for John who had never enjoyed William’s robust good health:

‘My official reason for returning home is to withdraw him [John] from the most eminent dangers to which he exposes himself … returning from his club at one or two in the morning …’

Whatever the slight frictions that may have been between them, they were very close, and John’s sudden death from rheumatic fever in 1828 changed everything. Their father, Laurence, was devastated. He wrote:

‘…everywhere I go, every object I see, every word that is spoken, every book that I read in some way or other reminds me of him…’

Friends and family recognised what a terrible loss John’s death was: A chest six feet long and two feet deep was required to hold all the letters of condolence the family received at the time. It stands on the first floor landing at Birr to this day, with a marble bust of John on top of it. Not only had William lost his closest companion but the burden of having to become what John himself might have been fell upon him. He was expected to console his father for the loss of the favourite. As a friend wrote to Laurence,

‘How happy it is for you to have such a son as Lord Oxmantown [William]. Consider how few parents have such a blessing, an eldest son distinguished among men of literature and science….’

The shadow this cast on William’s life was still apparent eight years after William’s own death, when his son addressed the crowd assembled at the unveiling of the memorial to William, in Birr town square, in March 1876,

‘Unhappily John Clere Parsons was cut off before his time, but his brother who was longer spared employed a good part of his time.’

From the time of John’s death there was another source of William’s resolve to achieve great things in the stars: He was living now for John as well as for himself, and perhaps he knew he must make a life good enough for the two of them.

*

Walk into the grounds of Birr today and at first sight the Leviathan will take your breath away. A vast, black tube between monumental walls, it seems somehow alive, just waiting to act. It is out of scale with the landscape, too big and strange to belong on Earth at all. Its vital statistics are astonishing: A speculum made of four tons of bronze, a barrel fifty eight feet long, of pitch pine and iron castings and weighing more than one hundred and fifty tons; held between stone walls, seventy feet long, and fifty feet high, controlled by a complex system of pulleys and chains. All of this is the more breathtaking and astonishing when you remember that it was made using nothing more than human ingenuity and muscle: No cranes, no hydraulic lifts, no computers, no scientific committees or government grants.

By the time William joined the Royal Astronomical Society in 1824, the great Herschel was dead (in August 1822), and his forty nine inch diameter telescope in disrepair. There was little immediate hope of exploring depths of the Universe or of finding the true identity of the two and a half thousand nebulae that Caroline Herschel had mapped. William must have felt from his early twenties that building a big telescope was the way forward for astronomy. William had begun experiments in astronomy in 1827, but the pace and intensity of the work grew after John’s death. This work wasn’t that of a star gazer, no long, lonely midnight vigils with a telescope. William’s astronomy began with the practical problems of designing and building a large reflecting telescope. The first stage in that process was the casting and polishing of a metal mirror, or speculum. William spent much of the time he wasn’t in Parliament in a forge he had built next to the castle, casting specula of various designs and in a range of different alloy mixes, and devising ways of polishing them. Weeks and months of experimentation and hard work went into every trial of a new allow, a new mirror design, or new method of polishing. The setbacks were constant: Alloys proved too brittle, causing mirrors to shatter, even as they were nearing completion after weeks of careful cooling and further weeks of polishing; Polishing methods turned out mirrors that were the wrong shape by a thousandth of an inch. To describe the work as painstaking is not enough: It was draining, emotionally and physically. Every time something went wrong William had to come with a new idea, his hope undaunted, and his enthusiasm undiminished. But he wasn’t merely emerging from his study to give orders, William laboured alongside the men he trained to help him. A visitor to the Castle, watching him rolling his sleeves up over his muscular, blacksmith’s arms, mistook him for an ‘intelligent foreman’.

William had been trained for precision, scientific thinking. But his mind was flexible too, so he had the ability to come up with innovative and creative solutions to the problems he encountered in building the telescopes. But even these gifts weren’t so unusual; what really set William apart was that his response to every setback, failure or problem was simply to work, and find a way around whatever was in his way. He achieved so much because of a quiet and invincible determination. Perhaps he felt John’s ghost at his shoulder urging him on, helping him keep his ultimate goal before him in his mind’s eye. Whatever it was, William was nothing if not focussed. He had read Herschel’s work on nebulae and how their form might relate to the evolution of stars and planets. He knew that only a very big telescope could look far enough into space to expand Herschel’s vision. And a very big telescope was what he was going to build.

As he wrote in 1830:

‘…there can be little doubt that discoveries will multiply in proportion as the telescope may be improved. It is perhaps not too much to expect that the time is not too far distant when data will be collected sufficient to afford us some insight into the construction of the material universe.’

William’s desire for ‘insight into the construction of the material universe’ was not an ego centric quest. Other telescope builders before him had sought to use their discoveries as a means to self aggrandisement. Those men kept secret the details of their lenses and mirrors, their alloys and their polishings. William published everything he discovered and opened his workshop to anyone who showed interest. As Romney Robinson, Director of the Armagh Observatory wrote of him:

‘It was not the mean desire of possessing what no other man possessed, of seeing what no other had seen, that induced him to bestow so many years on this pursuit; had such been his motives, he would have kept to himself his methods, instead of opening his workshop to all who had the slightest desire of following in his steps…his sole object is to extend the domain of astronomical knowledge.’

The Leviathan wasn’t born in a hurry, the child of one great explosion of energy and creativity. It was the result of nearly two decades of patient labour and meticulous experimentation by William and the team of workers he had assembled around him. There had been many steps and setbacks along the way, and William had patiently worked on every part of the process: The composition of the alloy, the methods of smelting, casting and cooling the speculum. He had even invented a new variety of steam engine just to drive the high precision polishing machine. All the skills he and his team needed to build the Leviathan were practised on the a smaller telescope with a three foot reflector that was completed in 1839.

The great telescope project was a strange mixture of exacting engineering science — the grinding of the mirror surface, for example, had to be done to tolerances of one ten thousandth of an inch — and construction on an heroic scale. The furnaces used to melt the bronze required two thousand cubic feet of turf, and ten hours burning to get them to the required temperature. The molten metal was held in three great crucibles each twenty four feet across and weighing half a ton when empty. It was very dangerous work, and only someone with William’s cool head for planning and forethought could have done it. All the same it wasn’t without its romance: On the night the Leviathan’s mirror was cast in April 1842 every one on the Demesne and many in the town must have been standing spectator. William’s enterprise was already injecting a special magic into their lives, as Romney Robinson, showed in his description,

‘The sublime beauty can never be forgotten…the sky crowded with stars and illuminated by the most brilliant moon, seemed to look down auspiciously on their work. Below, the furnaces poured out huge columns of nearly monochromatic yellow flame and the ignited crucible during their passage through the air were fountains of red light, producing on the towers of the castle and the foliage of the trees, such accidents of colour and shade as might almost transport fancy to the planets of a contrasted double star….’

William himself never gave in to outbursts of such purple prose, but his careful approach sometimes gave rise to moments of equal enchantment. The mirror was polished by William’s ingenious machine in the workshops just outside the Castle’s ‘back door’. Above the machine, trap doors opened to the sky, and a view of the adjacent tower and flagpole. The means of testing the quality of the mirror’s surface was by hoisting William’s watch to the top of the flagpole and examining its reflection in the mirror. Imagine after hours or even days of polishing, the trapdoor flung open to the sunlight, and a ring of anxious faces bent over the brilliant surface of the mirror. Some young apprentice is dispatched to run up the Tower steps with His Lordship’s pocket watch, and everyone stands anxiously awaiting the verdict, will the watch face be clearly readable in the speculum’s bowl of light?

Details of the Leviathan’s construction and the great hopes for its abilities were published in an article in the Illustrated London News in 1843. It was a tremendously bold move on William’s part, as he had no way of knowing in advance that the Leviathan really would be able to show anything of value. But within a a year of the article, he had the first indication of the telescope’s capabilities. The polishing process was complete and the mirror, the speculum, was ready. Its housing was not so it was given its first try propped up on a slope outside the Castle . This makeshift try-out was rather contrary to William’s usual painstaking careful approach, but it indicates the level of his excitement, and perhaps anxiety. How many assistants must it have taken to get the almost four tons of bronze manhandled into position and pointed at the sky? The results were better than William could have hoped; the Leviathan made its first discovery, a bright star, previously thought to be one object revealed itself clearly to be two.

The Leviathan was finished and ready for use in February 1845. William invited Dr Romney Robinson and Sir James South to Birr to give the telescope its first real trial. They waited round in the drizzly dusks, looking out anxiously for a break in the cloud cover, but it didn’t come until the fifteenth. Dressed in heavy overcoats and stovepipe hats the three men walked the five hundred yards from the castle to the telescope, and mounted the series of wooden staircases that took them to the viewing platform, a few feet from the Leviathan’s mouth. They stood suspended almost sixty feet above the ground and shouted instructions to the team of helpers who winched the barrel into place, like a giant gun taking aim. Sir James was very deaf and all conversations with him had to be at maximum volume, so the first use of the Leviathan wasn’t a peaceful contemplative experience. However they did make good observations of the double star Cator and the nebula M67. Then the weather closed in again and in the next few wet weeks the speculum sat idle in the damp, and tarnished . It had to be repolished, which meant dragging it across the estate to the workshops by the back door of the Castle, on a set of specially constructed rail tracks.

In March the telescope was officially opened. The ceremony included the Dean of the Church of Ireland walking the length of the barrel in top hat and raised umbrella. It wasn’t until April that the weather was clear enough for William to make continued observations.

At the start of his telescope building career fifteen years and more earlier William had not been a skilled observer. He was just a beginner, a mathematically gifted engineer still, rather than an astronomer. But he’d learnt through doing, making meticulous observations with his smaller telescope, and taking counsel from Robinson and South. By the time he stood on the Leviathan’s lofty perch on an unseasonably cold clear night in April 1845, he was one of the finest astronomical observers in Europe. He was ready, the man and his machine converged on their goal.

William, calling instructions to his assistants, went straight for one of the nebula that had fascinated him from the start. He looked at the nebula M51, first described by Herschel. He had worked and waited a long time for this moment, and he was rewarded immediately with a startling discovery, that would have been impossible without the huge, light-grabbing ability of the Leviathan. M51 wasn’t a cloud of glowing gas or mysterious ‘nebula material’ it was made of stars and what was more those millions of stars were arranged in a spiral , a form suggesting the motion of a whirlpool. William knew from the first moment how important the image he saw in telescope was. But with success now assured, his calm and caution returned. Over many clear nights in the Spring of 1845 he made drawings of M51. This was incredibly difficult. He was working in the dark, so his eyes would be at their most sensitive to the pale glimmering, ghosts in the telescope, and he had no means of measuring the proportions of the image. His only solution was to draw the M51 over and over again, until the image he had seen in the eye of the Leviathan matched that he made on the paper. The beauty of the resulting drawing is undeniable. Something of William’s own quiet, determined nature shows in it, there is a kind of tenderness with which he’s rendered its swirl and sweep. There’s no exaggeration in his picture, no ego. He felt himself to be a humble and privileged observer, his duty solely to bear honest witness to the wonders that he saw.

He showed his drawing at the June meeting of the British Association for the Advancement of Science that year. It created a sensation. The spinning aspect of Laplace’s theory seemed to have some truth, but M51 was clearly made of stars, not glowing ‘nebula material’ that might give rise to just a few planets. Some could not believe that such detail could be seen through any telescope, and said William had drawn an instrumental artifact. It was fifty years before William’s observations could be put beyond any speculation by the photographs of the astronomer Isaac Roberts. Only modern photographs of M51, the Whirlpool Galaxy, show how perfectly accurate William’s observation and record were. We now know that the Whirlpool is in fact two spiral galaxies turning around each other in a long orbit of a hundred million years, and William’s work was the foundation stone for that discovery. At the meeting President of the Association, John Herschel, the great astronomer’s astronomer son, knew the value of what William had done,

‘…an achievement of such magnitude that I want words to express my admiration for it.’

That achievement is is still recognised today as a milestone in astronomy,

‘He succeeded in an almost impossible task…the Birr Telescope is a tribute to the Earl’s skill in engineering and optics: results he obtained with it are such a remarkable tribute to his observational skill and insight that such a device would record more of the depths of the Universe than man had yet conceived…It is to the everlasting credit of Lord Rosse that he discovered the spiral nature of the nebulae and thereby opened an avenue of exploration which today has lead us into the inconceivable depths of space and time.’

— Professor Sir Bernard Lovell

It was the biggest and best discovery the Leviathan would ever make. Two months later the telescope was lying idle, the speculum’s bright eye was clouded with a fog of tarnish. At the very point at which his reward for years of work and planning was lying in William’s hands, it was snatched away. The Potato Famine, which William had warned of and predicted for three years and more, had hit. William couldn’t sit on his high platform searching the sky, whilst the people of Parsonstown were starving. He set astronomy to one side for three years and applied his determination to finding jobs and food for his desperate country men.

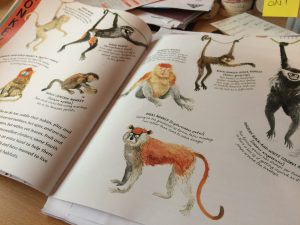

It was typical of William that the gap in consistent use of the Leviathan didn’t defeat him. As soon as the worst of the famine was over the mirrors — the main one and a spare — were repolished and the telescope was ready for action again in February 1848 and systematic observations could begin again. William engaged a series of astronomers to work at Birr and make observations over the next few years, so when he was otherwise engaged work could continue. William and his helpers concentrated their attention on the nebulae. They found other spiral galaxies amongst the list of nebulae, they found nebulae that resolved into starry galaxies that weren’t spirals and they found nebulae that didn’t resolve into stars at all and seemed to be truly nebulous clouds of brightness. William made beautiful and meticulous drawings of many of these objects which can can be seen today in the Birr archive. But he was of course cautious with his conclusions. Whilst Romney Robinson ran away with the idea that all nebulae were in fact masses of stars, and merely required ever larger telescopes to prove it, William formulated a view close to our modern knowledge of ‘nebulae’. We now know that some are clusters of stars within our own galaxy, some are true ‘nebulae’ clouds of dust and gas, some are single stars with a halo of gas, and some really are other galaxies. William made meticulous observations and drawings of all types such as: The faint hot star and its veil of gas called the Owl Nebula; the Orion nebula, a strange and complex patch of bright gas, birthplace of stars within our own galaxy; Messier 13, a bright patch in the constellation Hercules which emerges in the Leviathan’s eye as a cluster of stars; the Andromeda Spiral — which William guessed correctly was a ‘whirlpool’ galaxy which we were viewing edge on. What William couldn’t know at the time, without a means of measuring distance better than Herschel’s rough comparison of starlight, was that his telescope was reaching deep, deep into space and time. Just one of the many spiral galaxies he described is M77, the ‘blue spiral’ in the constellation Cetus. It is fifty million light years away.

*

In the years following the famine, Birr became the astronomical phenomenon of Europe. The Leviathans’s fame spread from Petersburg to Paris, and the name of Parsons with it.

Brendan Parsons, the present (7th) Earl of Rosse, told me that ‘Parsons’ marriages are made in Heaven’. But marriages made in Heaven must be maintained on Earth, and having a good example of marriage is always a helpful start. William certainly had that. His parents Laurence and Alice had adored each other. Laurence’s letters home from London are sweetly tender

‘…adieu my ever dearest of beings…’

‘…ever dear and adorable wife…’

‘…take care of yourself and take care of the children. When you are well, and they are well, all is well….’

So when William married Mary Wilmer Field in 1836, he had a good idea of what he was aiming for in married life.

Mary was thirteen years his junior, the daughter of generations of well-to-do country squires. She was by no means William’s social equal, but she had been well educated and had a fortune worth more than eighty thousand pounds. Right from the start, she showed that she was not going to be a shrinking and subservient wife. She redesigned the interior of her bedroom at Birr, and refused to move in until it was completed. She was a tartar with the servants, laying out their duties in meticulous detail, right down to the daily time table for the kitchen boy.

Mary wasn’t a spoilt brat or a monster. She’d lost her mother early on, following the birth of her sister Delia, and had been brought up by a governess, Susan Lawson. Miss Lawson remained a lifelong friend and she instilled in Mary an unshakeable belief in the value of discipline, hard work and order as the route to happiness and fulfilment. Mary quite simply wanted people to be happy, so she guided them to it the only way she knew how. She was bossy and controlling but she was also warm and loving. Her correspondence with her beloved Uncle Richard Wharton Myddelton, and her relationships with friends and family over the years show that there was big heart beating inside the iron determination. The Illustrated London News article that lauded the forthcoming Rosse Telescope took time to praise Mary’s talents,

‘She has with the most exquisite taste improved the grounds of the castle and freely opens them for their [the people of Parsonstown] accommodation … she has taken a lively interest in the poor and is constantly improving and changing to afford them work … the consequence of this conduct is that she is universally esteemed and looked up to, and that her town is almost free from the discontent and distress that is so rife in other places …’

Her intelligence and her strength made her a success in her formal role as the Countess of Rosse, and they also contributed to the success of their marriage. But the real secret of the ‘heaven made’ union was that she was interested in William’s work, excited by his astronomical ambitions. It was part of what had attracted her to him. Not only did her money help to finance the Leviathan, her enthusiasm helped to drive the project forward, not as a passive help mate, but as co-worker with projects and passions of her own. When William’s forges lay idle Mary stepped in and used them to make iron gates for the new stone Castle Keep that she had designed. When William abandoned photography as unsuitable for use with the Leviathan, she took it up and became an award-winning photographer. Her photographs won her the Photographic Society of Ireland’s Silver Medal in 1864, and a place in the Dublin International Exhibition in 1865. Many of her photographs still survive and open like a window onto the life of the Castle in the 1850s and 60s. There are her children in their best clothes staring solemnly into the camera, with her son Randal always blurred because he simply cannot sit still for the ten second exposure. Here are her friends, the natural historian Mary Ward, astronomer Romney Robinson, the explorer Captain Knox. There is the stable block she designed and had built, with ladies and gentlemen appropriately posed. You can imagine her standing behind her heavy wooden camera, calling to them to stand just so, and to keep absolutely still. And here is the glorious Leviathan itself, at the height of its fame, with two of her children and their governess posed cheekily in the mouth of the barrel.

I was shown Mary’s personal cabinet, an elegant and elaborate piece with many tiny ivory-fronted drawers, with her little treasures still stowed away inside it. Looking through all its drawers and crannies, I was struck by the some of the things she’d preserved as her most precious. They include a selection of musket balls and ancient coins found when the moat was re-dug and some little fossil collections, meticulously pasted onto the painted backs of her calling cards. There are tiny scale models of her building designs, made, once again, from her calling cards and painted with watercolours. They are the sort of things I’d expect to find in the treasure box of an bright, studious ten year old, the sort of things in fact I hoarded myself as a girl. That youthful core which had the capacity to be newly fascinated by the world and all that was in it, was I’m sure what bound her so closely to William.

They became a good team, Mary compensated for William’s rather shy manner, as Frances Power Cobbe spotted on a visit to Birr in the 1840s,

‘Lord Rosse is a heavy red faced, tow wigged man with a nervous twitch and awkward, though thoroughly obliging manners. Lady Rosse is a beautiful, gay, clever woman. She amused me greatly after dinner by saying that he was so terribly matter of fact that she could never make him understand punch…

‘They were’ she added later, ‘a very happy and united couple.’

They worked together to run the life of the Castle, to raise their children and, during the Famine, to save the people of County Offaly from its worst effects. During the famine William as Lieutenant of the County had to organise and distribute aid to the poor and starving. This involved raising money locally and generating work for small farmers who had left their land to find food. Mary and William found five hundred jobs on the Demesne, and the wages were paid from Mary’s fortune. As a result, the famine death toll in the Parsonstown region was far lower than in many other parts of the country, and any reservations that the local population might once have had about the Parsons family were utterly dispelled. As Randal, one of Mary’s youngest sons, said of the period following the famine

‘I can remember times of great unrest … my father used to go out to the telescope with pistols in his pocket … but there was never any real danger as the family was so popular…’

There was a story circulating in Irish society throughout the period of their marriage. It tells how William, on one of his fact-finding missions to an English manufacturing works in the North, was employed ‘incognito’ as a foreman. The ‘boss’ was so impressed with this new worker that he invited him for Sunday lunch. William and the boss’s daughter, Mary, fell for each other. But Mary’s father had better things in mind for her than a marriage to the shop floor. William was sent packing, only to return, in full Noble regalia, to ask Mr Field for his daughter’s hand.

Sadly, there’s not much chance that the story is factually correct, but there is a truth in it. William and Mary were, as Frances Cobbe said, ‘a happy and united couple’, they had the kind of equal, loving relationship that might be the envy of modern marriage. Their relationship is captured in a simple and rather ineptly rendered picture, painted by one of their many friends, the astronomer Piazzi Smyth. It shows a rather portly William and the dark haired and striking Mary, sitting at a table, turned to each other. In William’s hands are little renderings of his marvellous astronomical drawings, whilst Mary wears the gloves she used to protect her hands from darkroom chemicals. They are looking into each other’s faces with the same expression of rapt delight. They are not, I think, exchanging words of love, they are telling each other about nebulae and photographs, and what they will each do tomorrow.

Yet another of William’s inheritances was a love of family life. He and Mary had their children educated at home, and although there were always nannies and tutors on hand to help with the child care, the children were as much as possible included in the life of the Castle in the Winter, and of the London Season in the Summer.

Randal Parsons, one of William and Mary’s youngest sons, wrote a brief private memoir of the life at Birr in the 1840s and 50s when he was growing up. Through his rather restrained and guarded prose, a vivid picture of a very lively household emerges.

In typical style, Mary laid down a pretty strict schoolroom routine for the six sons living at home at that time, beginning with lessons at 7am. There was still, however, plenty of space for fun. William and his sons were known collectively as ‘the Boys’, they disappeared for long periods into William’s workshops, to emerge with all sorts of home made inventions, spring traps for rabbits, miniature steam engines and once, a giant magnet with which they picked up all the fire irons in the drawing room. Randal gives some indication of more frivolous activities: The Bishop of Limerick slipped and fell on the polished floor of the hall whilst playing shuttle cock and battledore, and was laid up at Birr for six weeks.

From the late 1840s the Leviathan became a celebrity, just as William had intended it to be. His intention had never been to keep the telescope for his own use to make ‘glorious discoveries’ on his own. All along he had had published every detail of the Leviathans’ construction so that others could follow in his footsteps and make telescopes for themselves. He threw open the doors of Birr to anyone who wanted to come and learn more about astronomy or the telescope itself. The viewing platforms on the Leviathan were built to take twelve at a time, and frequently were tested to their limits. Birr was always full of visitors, political and scientific friends, cousins, Aunts, Uncles, too. Many visitors came back to Birr time after time and stayed for long periods. In Frances Cobbe’s words,

‘… it seems the philosopher understands the art of good living for a better dinner I never ate!’

The frosty nights of Winter were best for observations and in Summer William’s duties took him and the family to London for ‘The Season’. There were parties and soirees almost every night at the Parson’s house in Connaught Place. William was elected President of the Royal Society in 1848 and from then on until his death in 1867 the Summer soirees at Connaught place were an important meeting place for scientists, musicians, artists and politicians.

After the Season came long visits to Grandmother Parsons in Brighton, and, in the 1860s, voyages aboard the Parsons’ yacht. Everyone went, including Mary and they sailed around the coasts of Britain and Europe. Randal and the eldest boy Laurence kept journals for one of those sailing summers. From Randal’s particularly, a real picture of family unity emerges: At some points it seems Randal got fed up with his diary and changes in handwriting happen mid-entry, as if the diary had been passed around the dinner table.

There was however another story behind the glittering Scientific and social success, the lively shared experiences of a happy family. There was tragedy in the family. Randal mentions it only in passing in his memoir , it was a place perhaps too sore to touch more firmly,

‘In my younger days Mother Father and six sons were living at home. Other children died in infancy and the only one who lived to any age was my sister Alice who died of rheumatic fever at 13 [sic] and I never saw her.’

Mary’s first child Alice was born in 1839 and her second, Laurence in 1840. In 1842 , the year the speculum for the Leviathan was cast, and in 1843, she gave birth to little girls, who didn’t live long enough to be christened. Little William was born in 1844, but she lost another infant just after birth in 1845, the year the telescope was completed and the Famine began. John came a year after that in 1846, but Alice died in 1847. Randal was born in 1848 then there was another baby who died in the first days of life in 1850, whilst William was away for long periods preparing for the Great Exhibition, in London. In 1851, the year of the Exhibition (where Mary bought a whole new set of commemorative plates for the Castle), Clere was born, and three years later her last child, Charles. Just when she must have thought the heartbreak of losing children must surely be over for her, her little boys William and John died within two years of each other in 1855 and 1857.

Of the fifteen years that included the period of the birth and fame of the Leviathan, Mary and William lost seven of their eleven children. This was another engine to drive their activity, work and plenty of it was the best distraction from grief.

That isn’t the end of the sadness in this story. The Leviathan itself brought disappointment into the very heart of what should have been the complete triumph of its achievements. The feature that made the Leviathan great, its vast bronze ‘eye’ was also its fatal flaw. In the damp cold of the Irish Winter the metal surface tarnished, dimming the telescope’s vision. It was a problem William had foreseen, and the reason he had made two mirrors for the telescope. But as the great telescope’s fame spread, and more and more visitors were drawn to Birr to ascend the vertiginous viewing platforms to watch the Leviathan perform, there wasn’t always time to change mirrors. A few observers experienced the telescope on very much less than peak form, and their derogatory comments were amplified by a press which delighted,even then, in throwing mud. A stain settled on the reputation of the Leviathan. Down the years this small, bad press was casually replicated in one text after another, until the received wisdom about the Leviathan of Parsonstown was that it was some sort of hopeful monster, stranded in an Irish bog. William and his glorious, triumphant quest became blurred and faded, like the image of a distant galaxy in the tarnished eye of his Leviathan.

Materials and Methods

Birr Castle, unlike other Great Irish houses, kept its archive on site. Many houses which sent their family papers to the National Library lost everything when that institution was damaged in the Civil War. Birr too lost some of the archive in the Civil War, when fire destroyed the library, but most was saved, and much of it relevant to this story. William’s astronomical diaries and drawings, his private and scientific correspondence, estate records and accounts are all there, together with a similar level of documentation for his father, Laurence. Many of Mary’s pictures are still intact, her darkroom is much as she left it, and there are pieces of her private correspondence, to her Uncle and friends. In addition to the material in the archive at Birr, there is the chest of letters about John Parson’s death in 1828. There are many portraits and drawings done of and by members of William’s generation of the Parsons family, in the private collections at Birr Castle, which the 7th Earl and Countess of Rosse have kindly made available to me.

Not everything that I’ll need is at Birr. The County Offaly Museum keeps copies of local papers covering the period I’m interested in, plus a huge amount of documentation about the Famine. I can look for traces of William and Mary in the correspondence of the politicians and scientists of the time who were their friends, such as Nassau Senior, Romney Robinson, Fox Talbot. Mary Ward, William’s cousin and very close family friend who spent long periods at Birr, also kept a diary, and I’m on its trail. ( As another ‘strand of wool’, Mary Ward was killed in an accident at Birr two years after William’s death, involving a steam carriage made by William’s sons and driven by their tutor). There may also be useful material in the Conway Papers held at Balliol College Library in Oxford. These cover the elopement of William’s younger sister Alicia with Edward Conroy, son of Sir John Conroy who was said to have been Queen Victoria’s mother’s lover, and possibly Victoria’s biological father.

I’ll also be taking astronomical advice from Sir Bernard Lovell and Sir Patrick Moore, both of whom have been closely involved with the most recent chapters in the Leviathan’s story. ( I’ll be finding an expert in nineteenth century handwriting to help me with William’s letters, his writing is very hard to read!)

In addition to the archive at Birr (to which I’ve been given very free access by Lord and Countess Rosse) there are published books about the telescope and the science of the Parsons family. Patrick Moore wrote ‘The Astronomy of Birr Castle’ in 1992 (sadly now out of print) and W. Garret Scaife wrote ‘From Galaxies to Turbines, Science Technology and the Parsons Family‘ (The Institute of Physics Publishing) in 2000. In 1989 there was a travelling exhibition of the photographs by Mary Parsons and an accompanying book ‘Impressions of an Irish Countess’ by David Davison, the world authority on Mary. There are several local publications on the history of Birr and the surrounding countryside and of course, many general texts on the history of Ireland (eg. Kee, 2003 ‘Ireland, A History’).

Any family over time generates stories that tangle together like strands of wool. Few stories have a definite beginning or a real end. Not even birth and death can top and tail a life neatly, as the story of that life starts long before it begins and may go on for generations after it ends. The story of the Leviathan began with Laurence’s decision to educate his boys at home, and Alice’s cleverness at sums. It continues today in a whole generation of telescopes, an era of astronomical awareness that grew from the scientific work at Birr and in the Leviathan itself, restored in reputation and physical reality and back just where William put it.

With all that said, the story of the Leviathan of Parsonstown is William and Mary’s story. Without the combination of their skills and attributes it would never have been completed and achieved what it did. They were an extraordinary couple and they lived in extraordinary times.