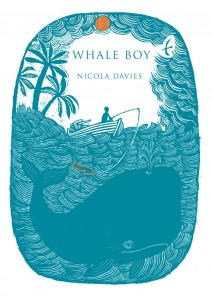

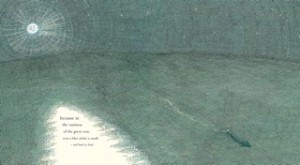

The title of ‘Whale Boy’ tells you pretty much what this book is about – a whale, in this case a young, wild, male, sperm whale, and a boy, Michael, who lives on a fictionalized Caribbean island. Over the last 35 years I’ve spent some of the happiest times of my life on board small boats watching whales, and I wanted to put the delight of those experiences and close encounters into the book.

Friendship with a wild animal is what I dreamed of most when I was little and I have enough contact with kids to know that many children today share that dream. So I’m hoping readers will relish the time that Michael spends in the company of his whale, and take those moments to their hearts. But ‘Whale Boy’ does not end in the way that many child and animal stories do. I won’t give anything away, but I will tell you a bit about what motivated me to write that ending, so you’ll understand when you get there, and I’ll also tell you about some of the other elements that shaped this book.

Whales and dolphins – cetaceans – have always had a special status in the hierarchy of wild creatures. Dolphins particularly have been considered intelligent and friendly for hundreds if not thousands of years; not just another creature. But in my lifetime whales and dolphins have acquired the status of religious icons, not only symbols of imperiled nature, but the embodiment of Mother Earth, a channel for the spiritual power of the universe. I’ve seen people play musical instruments to whales, sing to them, talk to them, swim with them, and I’ve heard people claim to be cured of every ailment from depression to cancer by contact with whales or dolphins. Businesses have grown up around these beliefs and every year thousands of people climb aboard boats, put on wetsuits or stand in the shallows waving a dead fish, in order to commune with some kind of cetacean.

Now I don’t dispute the cures, the benefits, the joys, the spiritual highs; for me, having a close encounter almost any wild animal is enough to keep me smiling and inspired for days, weeks, months even. But I do have a question and that is ‘what are the consequences for whales and dolphins of close contact with humans?’ I’m pretty sure a dolphin never claimed that smooching up to a human twelve year old healed a shark bite, or that a humpbacked whale never had a moment of life changing enlightenment after swimming with a dentist from Milwaukee.

What do cetaceans get out of our desire to be close to them? Well one thing they get is captivity. Even at its best and most closely regulated, captivity in a pool, for a creature whose natural environment is limitless, is not really acceptable. And remember, for every big, clean dolphinarium, there are at least twenty small, dirty, miserable little ponds where dolphins swim in circles for a few months and then die.

Another thing they get is disturbance. Harassment by boats can disrupt natural behavior and even put whales at risk of

injury from collision with propellors or other boat gear; many sperm whale tails show signs of past injuries. Motor boat noise is a potential source of disruption too, as whales and dolphins depend on sound for echolocation and communication. When cetaceans already have to put up with all our noise and bother in the sea as we transport goods around the globe or sonic ping the depths in search of minerals and oil, do we also have to pursue them in our spare time?

Swimming away is of course always an option, but this may cause a cetacean to use up valuable energy, or miss out on opportunities to feed or mate. One solution is to habituate cetaceans to human presence, or offer them a food reward. But even this can skew their behaviour in negative ways. In Western Australia, offspring of habituated dolphins show lower rates of survival than those of adults who have no contact with humans.

In Baja California grey whales on their breeding site seem to be the ones initiating contact with humans in boats. Boats wait, grey whales approach and if the occupants of the boat don’t interact, the whales move on. But this is a very special case. Contact in the breeding lagoons is well regulated, and grey whales have a very predictable migration route up the West coast of the United states, along whose entire length they are protected.

If grey whales think of humans as benign, they aren’t going to come to much harm.

For sperm whales, the species that I’ve been most involved with since 1984, helping out on my old friend’s research vessels in the Indian Ocean, Mexico and the Caribbean, the situation is very different. Sperm whales aren’t migratory, they’re just nomadic and wander, often very unpredictably, over whole oceans. The males especially travel over vast distances, that may span the tropics to the poles and back again many times in their long lives. They encounter all kinds of boats from huge tankers to little fishing boats, and all kinds of people from round the world yachtsmen to pirate whalers. For sperm whales to regard humans as benign is simply dangerous; for the whales, because they won’t always encounter well meaning humans, and for humans, because getting close to an animal the size of a bus is risky. The safest attitude for a sperm whale to take to any kind of human is one of deep suspicion and constant wariness.

When my friend Professor Hal Whitehead is studying sperm whales he keeps his vessel at a respectful distance, so as not to get in the whales’ way and uses sail rather than motor power whenever possible. Even so, there are times when the temptation to get very close to the whales is huge: young sperm whales, particularly young males, are very curious and will approach boats very closely. Looking down into the eye of a whale that is swimming round and round your boat, so close you could reach over side and touch it, really makes you want to get in the water with it; the whale itself seems to want you to. But every time this happens, what you have to ask is ‘ what good would it do the whale?’ and resist!

In Dominica, where I last spent time with sperm whales, there is a big temptation for people to try to get very close to the sperm whales that are found off the coast there. Every year more tourists come to see the sperm whales, and more boats promise to get them ever closer. Dominicans are not selfish or money grabbing but they are very proud of their whales and want to show them off to visitors. Whale watching operations bring people in boats very close to the whales, and even put tourists in the water with them. So although no one in Dominica has to face the dramatic decisions that Michael has to, perhaps someone needs to be asking what good do these activities do for whales? For example, would people be less likely to give to ocean conservation charities if they had got within 200m of a sperm whale rather than within 20 m? You wouldn’t expect to get out of your land rover and run over the Serengeti Plains with a cheetah, so why would expect to do something similar with a wild whale?

So that’s the big take home message of the book: an invitation for people to reflectt on what does close contact with a human mean to a whale – timely now in the light of the recent attention being given to captive Killer whales due to the excellent documentary ‘Blackfish’.

But there’s a lot more in ‘Whale Boy’ than an ecological message: every page has been marinaded in the sunlight, the warmth and the huge sense of community that exists in the Commonwealth of Dominica, (not the Dominican Republic as a typo in the first edition of the book states..grrr) where I spent two blocks of time whilst helping with a long term study of sperm whales, run by Hal’s colleague, Dr Shane Gero. Of all the places in the world I’ve been to, Dominica the one that most tempted me never to leave.

It is a truly extraordinary place. It has a population small enough for everyone to feel they have an identity as part of the country. That’s something we’ve lost in the UK and I really wanted to give my readers a taste of that sweetness of Dominican society.

Of course I wouldn’t presume to set a book in a real version of anywhere where I hadn’t spent at least a year, and I’ve spent less than two months in Dominica, so the island in ‘Whale Boy’ is an imaginary place. But I hope my imaginary island has the some of the flavour of real Dominica. In Dominica people sit on their doorsteps and chat, they lean over walls in the sunshine and watch the world go by, they ask ‘how are you?’ and truly expect an answer. Talking to people in Dominica is easy and listening to the musical pattern of their speech, the lovely old fashioned, poetic way they use English there, was a delight. I collected hundreds of gorgeous little snippets of conversation – here is just one I overheard in the street

“ And what are you doing’ in my territory this morning?” a tall gentlemen, smilingly asked a lady in a flowery frock and a little trilby hat

“Looking for you maybe?” she replied with a kind of sweet flirtatiousness she had clearly possessed in all of the seven decades since she turned fourteen.

He replied, open, gallant and equally flirtatious:

“So you have had an easy time of it, for here I am!”

I heard lots of other sorts of talking in Dominica, a French creole, a modern rap and Rasta speak, none of which I could follow or repeat, but I let the feel of those kinds of talk wash around me and leave a little water mark. Which I hope shows on the pages of ‘Whale Boy.’

Because Dominicans like to talk, doing research for the book there was a pleasure. I knew that fishing was to be a big part of Michael’s story so I took a walk round the fish market in the capital, Roseau one morning. I met Ishmael: greying at the temples and rather dashing. Over a table top of dismembered tuna, we began a discussion of the relative merits of being English or Dominican, both finally agreeing that to be Dominican was, overall, the better thing. When I said I wanted to know about fisheries on the island he whisked me upstairs to an office where Harold, a very senior person in the fisheries department, cancelled his appointments and spent an hour answering my questions.

I found out how the ecology and marine geography of the island mesh with history, economics and culture to shape the lives of the island’s fishermen.

“Small islands like Dominica”, Harold told me, “fish very efficiently. We don’t have any waste. Nothing is thrown back, there is no by catch. Everything is caught, brought to shore and sold or even eaten on the same day.”

Compared with the millions of tons of fish thrown away, the turtles, seabirds, cetaceans killed by the big scale fisheries of other countries Dominica is a model of good practice.

In Dominica no one can afford huge hydraulic winches and the other heavy duty gear that goes with big gill nets and

longlines of miles in length. The poorest people fish inshore with a net that perhaps twenty people pull out into a bay and haul back. Everyone gets a share even if they don’t own the net. This type of fishery is still a big cohesive factor binding communities together and providing a livelihood for those who have no other source of income, women, the very young, the very old, the landless. A small boat with two people can put fish traps down in water as deep as sixty meters and bring enough fish to take to market or feed a family. More prosperous fishermen who can afford a boat big enough to get out five or ten miles from shore also fish on a manageable scale: using hooks and lines, out at dawn, back by tea time, sold out by supper and then home. Nothing wasted, nothing caught that you didn’t mean to.

And there’s another factor that makes Dominican fisheries safe as well as efficient. Even those fishermen with boats and outboards don’t go out to sea for days on end, and they are hardly ever out at night, when most mishaps take place,

“The women are the anchor here,” Harold told me with a smile, ” Dominican fishermen like to come home to their wives at night”

So fishing, like everything else in Dominica is an expression of community.

There is one other big factor in Michael’s story that I was aware of it the moment I stepped on my first flight to Roseau, with a planeload of Dominicans coming home for Carnival: separation. Families across the Caribbean, have lost family members as people left to find work and new lives in the UK, America and all over the world. I met people who had left and would never return, and people who had made the choice to stay, and live a simpler life – all stories told to me with typical Dominican panache and style!

So many good things happened to me in Dominica, so many chance encounters and moments of shared laughter. The greatest compliment I think I’ve ever been paid was when a lady I was dancing with on the street at Carnival told me

“In your heart darlin’ you are Dominican”.

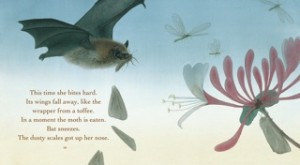

Dominica is the most loving place I’ve ever been to, so it’s not surprising that ‘Whale Boy’ is also about love, and how, when you love someone or something, you’ll do whatever it takes to protect it, and that’s the discovery that Michael makes.

But if you want to know more, you’ll have to read it!

I’m off to America tomorrow. Funny how travel never seems real when you write the words and only when you get on the plane. I’ll be traveling round schools in upstate New York talking to hundreds of children about animals and conservation and writing, focussing on my non fiction books. Narrative non fiction is huge in America and has just been shifted to the centre of the curriculum. Some bright spark in the Obama administration suddenly sussed what I’ve been telling teachers, editors, children …anyone who would listen…for years, that reading and writing non fiction teachers the most transferrable of skills: how to assimilate information and communicate it in an audience appropriate way. What the new curriculum (the Core Curriculum Standards) in the US acknowledges is that reading narrative non fiction, that has an opinion and a definite voice, encourages children to question how the writer knows what they know, what they think about it and why, as well as absorbing the facts packaged in the narrative. These skills of analysis and enquiry are hugely important and useful in every area of adult life from getting a degree to speaking to your boss about your performance, or explaining to your children why they need to wash their hands. We are bombarded by information, by data, by voices telling us things, so children need to practice assessing what they are told so they can sift the sense from nonsense, and conjecture from evidence. (I would venture to suggest that had Michael Gove had such a training he might be better at his job now).

I’m off to America tomorrow. Funny how travel never seems real when you write the words and only when you get on the plane. I’ll be traveling round schools in upstate New York talking to hundreds of children about animals and conservation and writing, focussing on my non fiction books. Narrative non fiction is huge in America and has just been shifted to the centre of the curriculum. Some bright spark in the Obama administration suddenly sussed what I’ve been telling teachers, editors, children …anyone who would listen…for years, that reading and writing non fiction teachers the most transferrable of skills: how to assimilate information and communicate it in an audience appropriate way. What the new curriculum (the Core Curriculum Standards) in the US acknowledges is that reading narrative non fiction, that has an opinion and a definite voice, encourages children to question how the writer knows what they know, what they think about it and why, as well as absorbing the facts packaged in the narrative. These skills of analysis and enquiry are hugely important and useful in every area of adult life from getting a degree to speaking to your boss about your performance, or explaining to your children why they need to wash their hands. We are bombarded by information, by data, by voices telling us things, so children need to practice assessing what they are told so they can sift the sense from nonsense, and conjecture from evidence. (I would venture to suggest that had Michael Gove had such a training he might be better at his job now).